Generative AI in Science: Revolutionizing Discovery and Innovation

Generative AI is transforming scientific discovery, accelerating drug development, designing novel materials, and unraveling biological mysteries. Explore how this technology is moving from potential to practical reality.

This is a fascinating time to be involved in artificial intelligence. While generative AI has captured public imagination with its ability to create stunning images, compelling text, and even realistic video, its most profound impact might be unfolding behind the scenes, in the hallowed halls of scientific discovery. Far from merely generating art, generative AI is revolutionizing how we approach some of humanity's grandest challenges: accelerating drug discovery, designing novel materials, and unraveling the mysteries of biological systems.

Imagine a world where new life-saving medicines are discovered in months instead of decades, where materials with unprecedented properties are engineered on demand, and where scientific breakthroughs are no longer limited by human intuition or painstaking trial-and-error. This isn't science fiction; it's the promise of generative AI in science, a field rapidly transitioning from theoretical potential to practical reality.

The Dawn of Generative Science: A Paradigm Shift

For centuries, scientific discovery has largely been an iterative process of hypothesis, experimentation, and observation. While incredibly successful, this method is often slow, resource-intensive, and prone to failure. The sheer combinatorial space of possible molecules, proteins, or material compositions is astronomical, making exhaustive search impossible.

Generative AI offers a paradigm shift. Instead of merely analyzing existing data, these models learn the underlying principles and patterns governing scientific phenomena. They can then generate novel candidates – molecules, proteins, materials, or reaction pathways – that are optimized for specific desired properties, effectively performing "inverse design." Given a target function or property, the AI proposes the structure that fulfills it.

This capability is fueled by the explosive growth of deep learning techniques, particularly those that have excelled in other generative tasks:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Pioneering architectures for learning latent representations and generating new data points.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): Agents learn to "build" or "modify" structures step-by-step, receiving rewards for achieving desired properties.

- Transformer Architectures: Originally for natural language processing, their ability to model long-range dependencies makes them powerful for sequences (like protein sequences or SMILES strings) and even graph-based data.

- Diffusion Models: The latest sensation, these models learn to reverse a diffusion process, gradually transforming noise into coherent data. They are proving exceptionally powerful for high-fidelity, diverse, and conditional generation across various scientific domains.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Molecules and many materials are naturally represented as graphs, making GNNs ideal for learning their complex relationships and generating new graph structures.

Let's dive into the specific scientific frontiers where generative AI is making waves.

Generative AI for Molecular Design: Engineering Life's Building Blocks

The ability to design molecules with specific functions is at the heart of drug discovery and materials science. Traditionally, this involves screening vast libraries of compounds or relying on expert intuition. Generative AI offers a more targeted and efficient approach.

The Challenge of Molecular Design

Molecules are complex entities. Their properties (e.g., solubility, toxicity, binding affinity to a target protein, synthetic accessibility) are determined by their atomic composition and three-dimensional structure. The chemical space – the set of all possible drug-like molecules – is estimated to be over $10^{60}$, making brute-force search impossible.

How Generative AI Steps In

Generative models learn the "grammar" of chemistry from large datasets of known molecules. They can then propose new molecular structures that adhere to chemical rules while optimizing for desired properties.

-

Representing Molecules for AI:

- SMILES Strings: A linear text-based representation (e.g.,

CCOfor ethanol). Useful for transformer-based models. - Molecular Graphs: Atoms as nodes, bonds as edges. Ideal for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

- 3D Coordinates: Crucial for understanding molecular interactions and binding.

- SMILES Strings: A linear text-based representation (e.g.,

-

Key Generative Approaches:

- GNNs for Graph Generation: GNNs can learn to add or remove atoms and bonds, or modify existing ones, to generate novel molecular graphs. For example, a GNN might be trained to predict the next atom and bond type to add to a growing molecular fragment, conditioned on desired properties.

- VAEs and GANs for Latent Space Exploration: These models map high-dimensional molecular representations into a continuous, lower-dimensional latent space. New molecules can be generated by sampling from this latent space and decoding them back into molecular structures. This allows for smooth interpolation between molecules and property optimization through gradient descent in the latent space.

python

# Conceptual pseudo-code for latent space optimization # (Not executable, illustrates the idea) latent_vector = model.encode(initial_molecule) for _ in range(num_optimization_steps): predicted_property = property_predictor(model.decode(latent_vector)) gradient = compute_gradient(predicted_property, latent_vector) latent_vector += learning_rate * gradient # Move towards better property optimized_molecule = model.decode(latent_vector)# Conceptual pseudo-code for latent space optimization # (Not executable, illustrates the idea) latent_vector = model.encode(initial_molecule) for _ in range(num_optimization_steps): predicted_property = property_predictor(model.decode(latent_vector)) gradient = compute_gradient(predicted_property, latent_vector) latent_vector += learning_rate * gradient # Move towards better property optimized_molecule = model.decode(latent_vector) - Reinforcement Learning for Step-by-Step Construction: An RL agent can learn a policy to construct molecules atom-by-atom or fragment-by-fragment. The reward function guides the agent towards molecules with high desired property scores. This is particularly effective for navigating complex chemical rules and optimizing multiple objectives.

- Diffusion Models for 2D and 3D Generation: Diffusion models are emerging as powerful tools. They can generate 2D molecular graphs by iteratively denoising a noisy graph representation. More excitingly, they can directly generate 3D molecular structures, which is critical for understanding how drugs bind to targets. For instance, a diffusion model might learn to generate a stable 3D conformer of a molecule, or even generate a molecule within a specified protein binding pocket.

Practical Applications:

- De Novo Drug Design: Generating entirely new chemical entities with improved efficacy, reduced side effects, and better pharmacokinetics.

- Lead Optimization: Taking an existing drug candidate and proposing modifications to enhance its properties.

- Targeted Library Generation: Creating focused libraries of molecules likely to interact with a specific biological target.

Generative AI for Protein Design: Engineering Nature's Machines

Proteins are the workhorses of biology, responsible for everything from catalyzing reactions to fighting infections. Designing novel proteins with specific functions is a holy grail in biotechnology and medicine.

The Complexity of Protein Design

Proteins are long chains of amino acids that fold into intricate 3D structures. This structure dictates their function. Predicting how a sequence folds (the protein folding problem) and, conversely, designing a sequence that folds into a desired structure and performs a specific function (the inverse protein folding problem or protein design problem) are immensely challenging.

How Generative AI Transforms Protein Engineering

Generative AI models are learning the complex interplay between protein sequence, structure, and function from vast biological datasets.

-

Proteins as Language:

- Large Language Models (LLMs) for Proteins: Inspired by NLP, models like Meta's ESM-2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) are trained on billions of protein sequences. They learn evolutionary constraints, structural patterns, and functional relationships. These protein LLMs can then be used to:

- Generate novel protein sequences.

- Predict the effect of mutations.

- Even infer protein structure from sequence.

- The core idea is that the "language" of proteins (amino acid sequences) encodes rich information about their biology.

- Large Language Models (LLMs) for Proteins: Inspired by NLP, models like Meta's ESM-2 (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) are trained on billions of protein sequences. They learn evolutionary constraints, structural patterns, and functional relationships. These protein LLMs can then be used to:

-

Diffusion Models for Structure Generation:

- De Novo Protein Structure Generation: Diffusion models are proving revolutionary here. Models like RFdiffusion (RosettaFold Diffusion) can generate novel protein backbone structures directly from noise. This is a monumental leap, as it allows for the creation of protein folds that may not exist in nature but possess desired structural motifs.

- Conditional Protein Design: RFdiffusion and similar models can also design proteins conditioned on specific criteria, such as:

- Generating a protein that binds to a particular target molecule (e.g., an antibody fragment binding to a viral protein).

- Designing a protein to adopt a specific shape or incorporate a particular functional site.

- This often involves iteratively refining a noisy 3D structure, guided by a loss function that encourages desired properties (e.g., structural stability, binding interface complementarity).

Practical Applications:

- Therapeutic Protein Design: Creating novel antibodies, enzymes, or peptides for treating diseases. For example, designing an enzyme that can break down plastic or a therapeutic protein that targets cancer cells.

- Vaccine Development: Designing antigens that elicit a strong immune response.

- Industrial Enzymes: Engineering enzymes with enhanced catalytic activity, stability, or specificity for applications in biofuels, detergents, or chemical synthesis.

- Biomaterials: Designing proteins that self-assemble into novel biomaterials with tailored properties.

Generative AI for Reaction Prediction & Synthesis Planning: Automating Chemical Synthesis

Beyond designing molecules, generative AI is also streamlining the process of making them. Chemical synthesis is often a bottleneck in drug discovery, requiring expert chemists to devise multi-step reaction pathways.

The Challenge of Chemical Synthesis

- Reaction Prediction: Given a set of reactants, what are the products? This can be complex due to side reactions, stereochemistry, and reaction conditions.

- Retrosynthesis: Given a target molecule, what are the starting materials and reaction steps needed to synthesize it? This is an inverse problem with an enormous search space.

How Generative AI Accelerates Synthesis

Generative models, often leveraging transformer architectures and graph-based approaches, are learning the rules of chemical reactivity.

-

Reaction Prediction:

- Sequence-to-Sequence Models: Treating reactants and products as sequences (e.g., SMILES strings), transformer models can be trained to predict the product sequence given the reactant sequence.

- Graph-based Models: Representing molecules as graphs, GNNs can learn to predict how graphs transform during a reaction, identifying bond breaking and formation events.

-

Automated Retrosynthesis:

- Reinforcement Learning: An RL agent can explore the retrosynthetic "tree," working backward from the target molecule to simpler precursors. Rewards can be based on the synthetic accessibility and cost-effectiveness of the proposed pathways.

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): Combined with deep learning models, MCTS can efficiently explore the vast space of possible retrosynthetic routes, guiding the search towards promising pathways.

- Transformer-based Retrosynthesis: Models can predict the reactants needed for a specific transformation to create a target molecule, effectively learning the inverse of a chemical reaction.

Practical Applications:

- Accelerated Drug Development: Quickly generating feasible synthetic routes for novel drug candidates.

- Automated Chemistry Labs: Integrating AI-generated synthesis plans with robotic platforms for fully autonomous chemical synthesis, creating a "self-driving lab."

- Chemical Process Optimization: Identifying more efficient, safer, or greener synthetic routes for industrial chemicals.

Generative AI for Materials Science: Designing the Future's Building Blocks

From superconductors to catalysts, new materials are foundational to technological progress. Generative AI is extending its reach to design novel inorganic and organic materials with unprecedented properties.

The Complexity of Materials Discovery

Materials science deals with a vast array of structures (crystals, amorphous solids, polymers) and properties (electrical, thermal, mechanical, optical). Discovering new materials with specific combinations of these properties is extremely challenging.

How Generative AI Unlocks New Materials

Similar to molecular design, generative models learn the relationships between material structure and properties from databases like the Materials Project.

-

Representing Materials:

- Crystal Graphs: For inorganic materials, unit cells can be represented as graphs where atoms are nodes and bonds represent interatomic distances.

- Compositional Vectors: Encoding the elemental composition.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Outputs: High-fidelity simulations providing electronic structure and energy.

-

Generative Approaches:

- GNNs for Crystal Structure Generation: GNNs can generate new crystal structures by iteratively adding atoms to a unit cell, predicting their positions and bonding environments, conditioned on desired properties like band gap or stability.

- VAEs/GANs for Latent Space Exploration: Learning a latent space of material compositions and structures allows for the generation of novel materials by sampling and decoding.

- Diffusion Models: Emerging for generating novel crystal structures or even amorphous material configurations, often guided by property predictors.

Practical Applications:

- Battery Materials: Designing electrodes and electrolytes with higher energy density, faster charging, and longer lifespan.

- Catalysts: Discovering more efficient and selective catalysts for industrial chemical processes, reducing energy consumption and waste.

- Superconductors: Searching for materials that exhibit superconductivity at higher temperatures and pressures.

- High-Strength Alloys: Designing lightweight, durable materials for aerospace and automotive industries.

- Thermoelectric Materials: Creating materials that efficiently convert heat into electricity and vice versa.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

While the promise is immense, several challenges must be addressed for generative AI to fully realize its potential in scientific discovery:

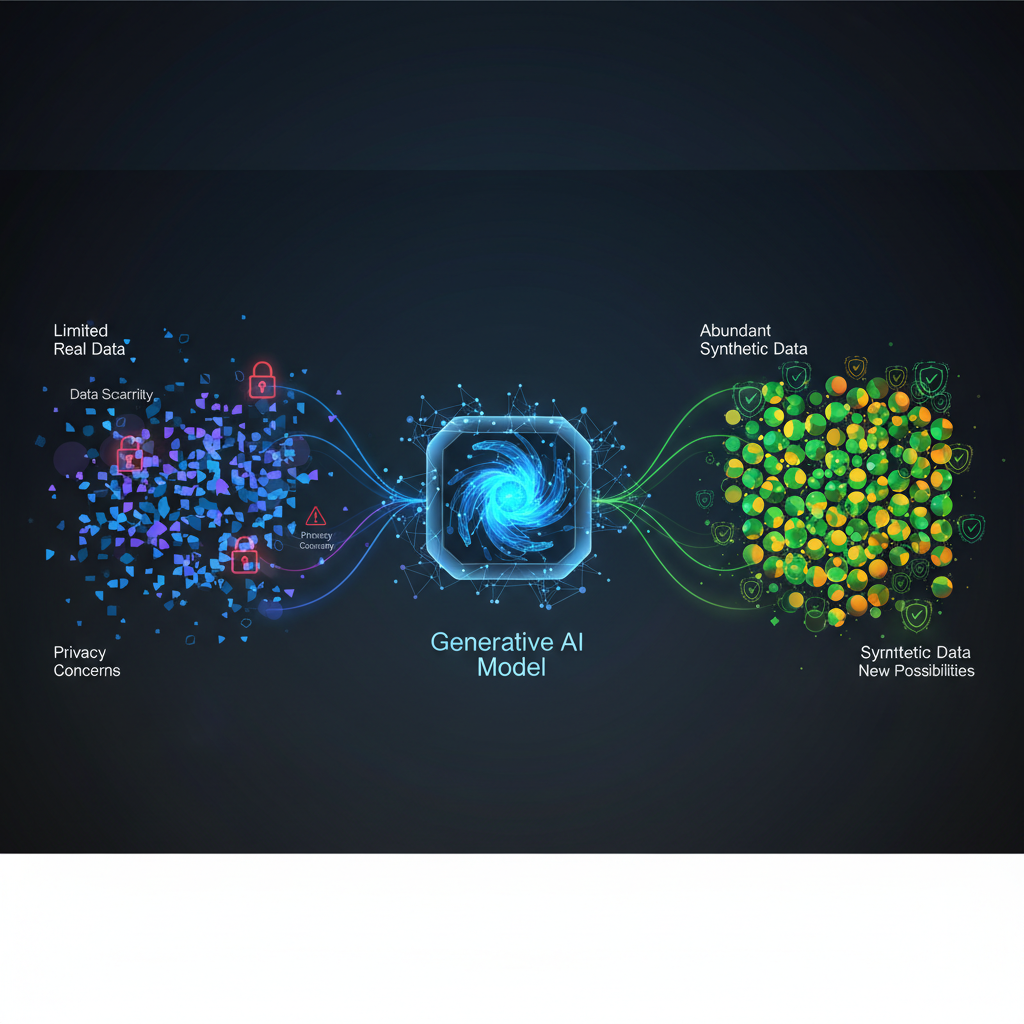

- Data Scarcity and Quality: High-quality, experimentally validated data is often limited and expensive to acquire. Many generative models thrive on massive datasets, which are not always available in scientific domains.

- Experimental Validation Bottleneck: AI can propose millions of designs, but each still requires costly and time-consuming experimental validation. This bottleneck limits the speed of the "design-make-test-analyze" cycle.

- Interpretability and Explainability: Understanding why a model generated a particular design can be crucial for scientific insight and for debugging failed experiments. Black-box models are less desirable in scientific contexts.

- Synthetic Accessibility and Manufacturability: A generated molecule or material might be theoretically ideal but impossible or prohibitively expensive to synthesize or manufacture in practice. Integrating synthetic feasibility directly into the generative process is an active area of research.

- Multi-objective Optimization: Real-world problems often involve optimizing multiple, often conflicting, properties (e.g., drug potency vs. safety, material strength vs. weight). Balancing these objectives is complex.

- Integration with Automation (AI for Science Labs): The ultimate vision is a closed-loop system where AI designs, robots synthesize and test, and AI analyzes the results to iterate. Building these "self-driving labs" requires seamless integration of AI with laboratory automation.

- Ethical Considerations: Particularly in drug discovery, ensuring responsible development, avoiding bias, and addressing potential dual-use concerns are paramount.

Conclusion: A New Era of Discovery

Generative AI is not just another tool; it's a fundamental shift in how we approach scientific discovery. By empowering machines to not just analyze but create, we are entering an era where the pace of innovation can accelerate dramatically. From designing life-saving drugs to engineering sustainable materials, the applications are profound and far-reaching.

For AI practitioners, this field offers a thrilling opportunity to apply cutting-edge deep learning techniques to problems with tangible, world-changing impact. For scientists, it provides a powerful co-pilot, augmenting human intuition and accelerating the journey from hypothesis to breakthrough. The synergy between advanced AI and domain-specific scientific knowledge is unlocking new frontiers, promising a future where the most challenging scientific puzzles are solved not just by human ingenuity, but by a powerful partnership between human and artificial intelligence. The next great scientific discoveries may well be generated by an algorithm.