Foundation Models in Computer Vision: Reshaping How Machines See

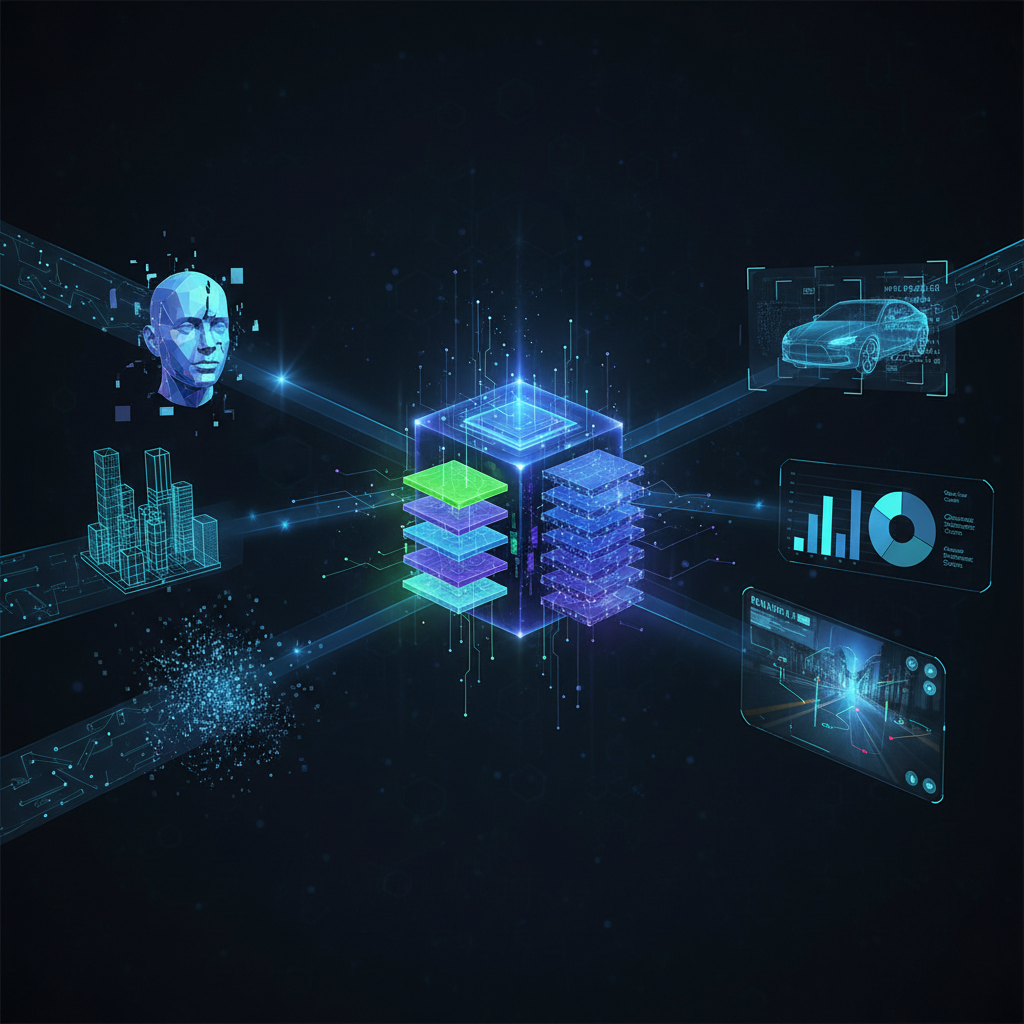

Explore the revolutionary impact of foundation models, particularly Vision Transformers (ViTs), on computer vision. Discover how these models are fundamentally changing AI architecture, training, and application, driving unprecedented scalability and multi-modal intelligence.

The landscape of artificial intelligence is in a perpetual state of evolution, with breakthroughs constantly redefining what's possible. In recent years, no area has seen a more profound paradigm shift than computer vision, driven by the emergence of foundation models. Just as large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and BERT revolutionized Natural Language Processing (NLP), a new breed of vision models, spearheaded by Vision Transformers (ViTs), is fundamentally reshaping how machines "see" and interpret the world. This isn't merely an incremental improvement; it's a foundational change in architecture, training methodology, and application, ushering in an era of unprecedented scalability, generalization, and multi-modal intelligence.

For AI practitioners and enthusiasts alike, understanding this transformation is not just beneficial—it's essential. These models are not only achieving state-of-the-art performance across a myriad of tasks but are also unlocking entirely new capabilities, from zero-shot image classification to generating photorealistic images from text descriptions. Let's dive deep into the technical underpinnings, key advancements, and practical implications of foundation models in computer vision.

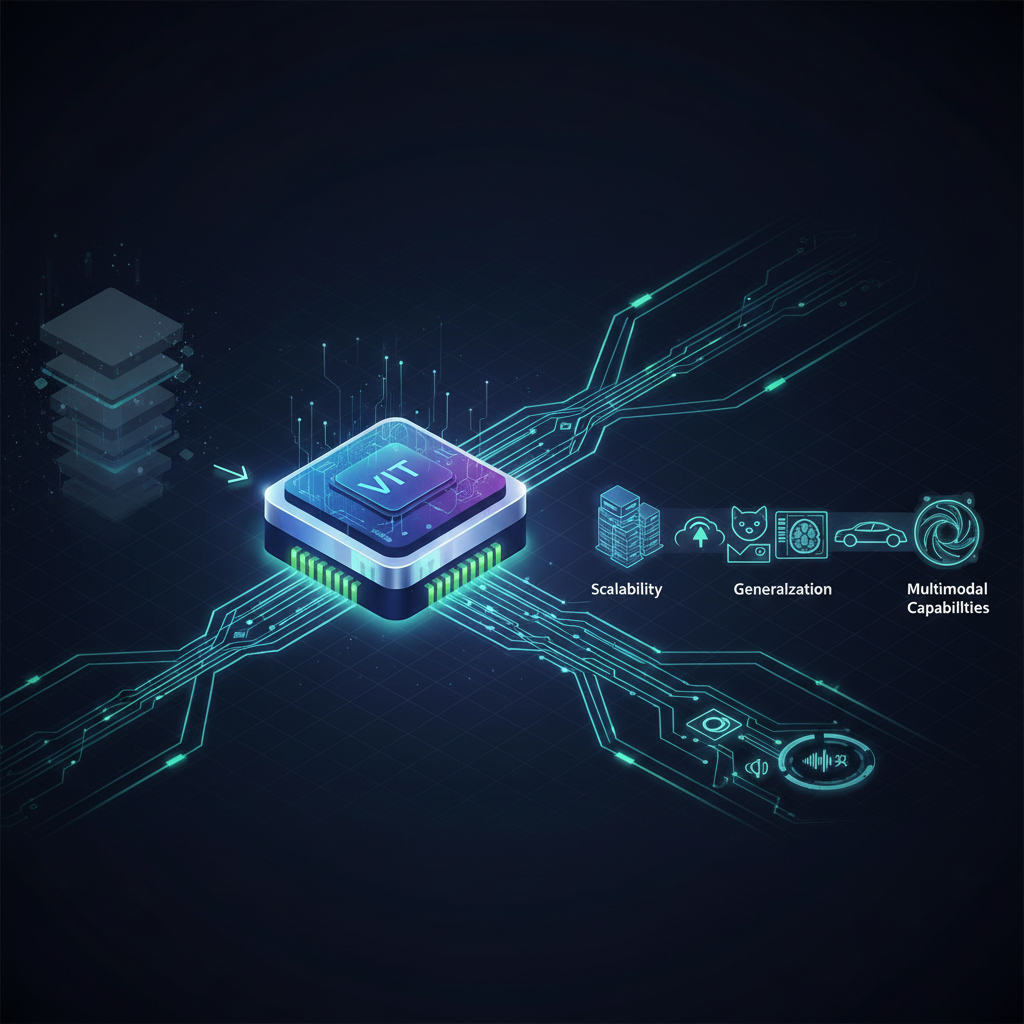

The Dawn of Vision Transformers: A Paradigm Shift

For decades, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were the undisputed champions of computer vision. Their hierarchical structure, local receptive fields, and translational equivariance made them incredibly effective at tasks like image classification, object detection, and segmentation. However, the Transformer architecture, originally designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks in NLP, presented a different approach: one that prioritized global attention mechanisms over local convolutions.

The seminal paper, "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale" (ViT), published in 2020 by Google Brain, challenged the CNN hegemony. The core idea was surprisingly simple yet profoundly impactful: treat an image not as a 2D grid of pixels, but as a sequence of flattened 2D patches, much like words in a sentence.

Here's how ViTs work:

- Patch Embedding: An input image is divided into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels). Each patch is then flattened into a 1D vector.

- Linear Projection: These flattened patch vectors are linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space.

- Positional Embeddings: Since Transformers inherently lack information about the spatial arrangement of input tokens, learnable positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings to retain spatial context.

- Transformer Encoder: The sequence of patch embeddings (along with a special

[CLS]token, similar to BERT, used for classification) is then fed into a standard Transformer encoder. This encoder consists of multiple layers, each comprising a multi-head self-attention (MHSA) module and a feed-forward network (FFN). The MHSA allows each patch to attend to every other patch in the image, capturing global dependencies. - Classification Head: For classification tasks, the output corresponding to the

[CLS]token from the Transformer encoder is passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) head.

While initial ViTs required massive datasets (like JFT-300M) to outperform CNNs, subsequent innovations quickly addressed this. Data-efficient image Transformers (DeiT) introduced a "distillation token" and knowledge distillation techniques, allowing ViTs to achieve competitive performance with much smaller datasets, even ImageNet-1K, without external data.

The Swin Transformer further refined the ViT architecture, making it more suitable for dense prediction tasks (like object detection and segmentation) that require multi-scale feature representation. Swin Transformers introduced:

- Hierarchical Feature Maps: Similar to CNNs, they produce hierarchical feature maps, allowing for multi-scale processing.

- Shifted Windows: Instead of global attention, Swin Transformers compute self-attention within local, non-overlapping windows. To enable cross-window connections and capture global context, these windows are shifted between successive layers. This significantly reduces computational complexity while retaining the benefits of attention.

These advancements demonstrated that Transformers could not only match but often surpass CNNs across a broad spectrum of vision tasks, especially when scaled with large datasets and efficient training strategies.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): Unlocking the Power of Unlabeled Data

Training foundation models requires an enormous amount of data. For vision tasks, obtaining vast quantities of high-quality, labeled images is incredibly expensive and time-consuming. This bottleneck led to the resurgence and rapid development of Self-Supervised Learning (SSL), a paradigm where models learn powerful representations from unlabeled data by solving pretext tasks.

SSL has been a critical enabler for vision foundation models, allowing them to pre-train on billions of images without human annotations, then fine-tune on smaller, labeled datasets for specific downstream tasks. Key SSL approaches for vision include:

-

Contrastive Learning:

- Core Idea: Learn representations by bringing "positive pairs" (different augmented views of the same image) closer together in the embedding space, while pushing "negative pairs" (views of different images) apart.

- Examples:

- MoCo (Momentum Contrast): Uses a momentum encoder and a queue of negative samples to enable large and consistent dictionaries for contrastive learning.

- SimCLR (A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations): Emphasizes strong data augmentation, a non-linear projection head, and a large batch size.

- DINO (Self-supervised Vision Transformers with out supervision): A self-distillation method where a "student" ViT learns from a "teacher" ViT (an exponentially moving average of the student). DINO famously showed that ViTs trained with this method could learn emergent properties like object segmentation without explicit supervision, producing sharp segmentation masks.

-

Masked Image Modeling (MIM):

- Core Idea: Inspired by Masked Language Modeling (MLM) in NLP (e.g., BERT), MIM involves masking out a significant portion of an image's patches and then training the model to reconstruct the missing information.

- Examples:

- MAE (Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners): Developed by Meta AI, MAE masks out a very high percentage (e.g., 75%) of image patches and trains a ViT encoder to reconstruct the original pixel values of the masked patches from the unmasked ones. MAE has demonstrated remarkable scalability, learning high-quality representations that transfer exceptionally well to downstream tasks.

- BEiT (BERT Pre-training of Image Transformers): Similar to MAE, BEiT uses a discrete VAE to tokenize images into "visual tokens" and then predicts the masked visual tokens.

SSL methods, particularly MIM, have proven incredibly effective for pre-training ViTs, allowing them to learn robust, generalizable features that capture the semantic content of images without relying on expensive human labels.

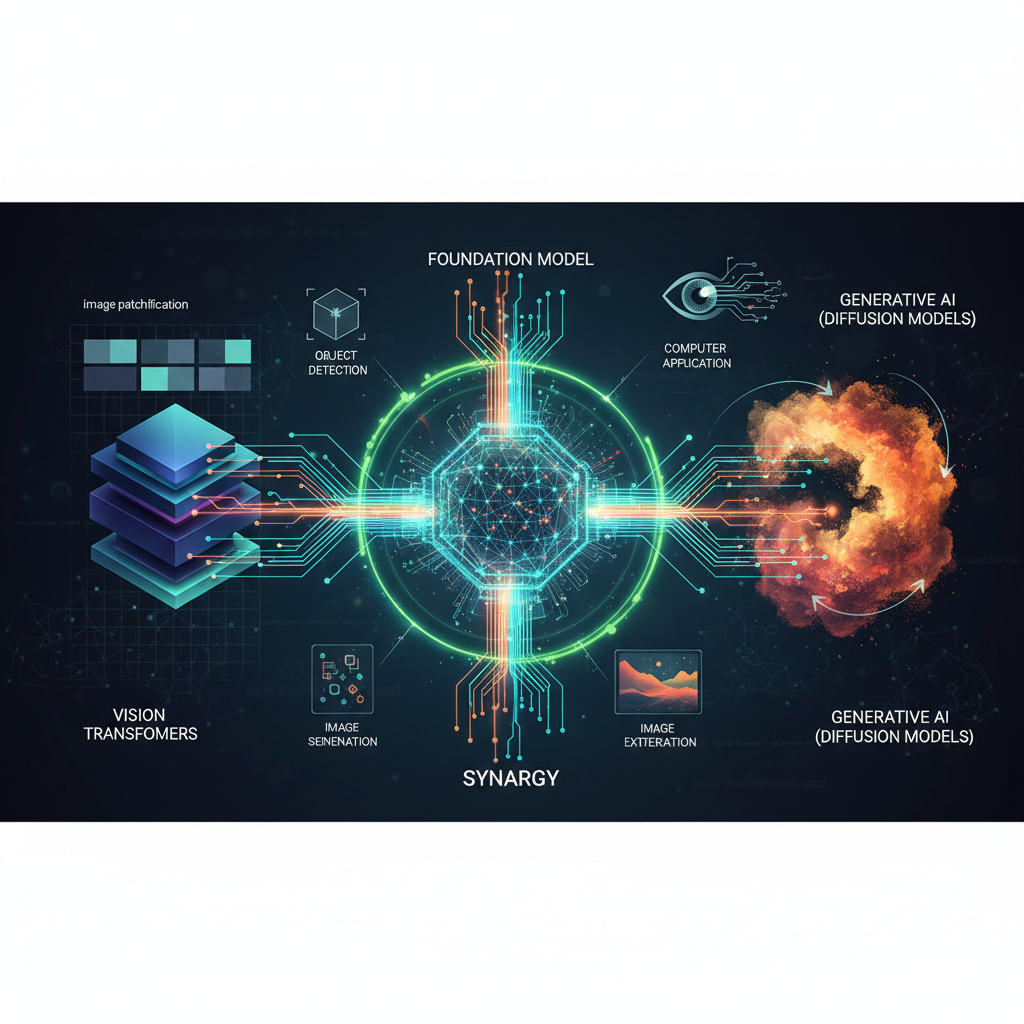

Multi-Modal Foundation Models: Bridging Vision and Language

Perhaps the most exciting frontier in AI is the convergence of different modalities, especially vision and language. The Transformer architecture's flexibility makes it uniquely suited for this, leading to the development of multi-modal foundation models that can understand, generate, and reason across both images and text.

-

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training):

- Developer: OpenAI

- Mechanism: CLIP learns robust representations by training on a massive dataset of 400 million image-text pairs scraped from the internet. It uses a contrastive learning objective to jointly train an image encoder (a ViT or ResNet) and a text encoder (a Transformer) to maximize the cosine similarity between correct image-text pairs and minimize it for incorrect pairs.

- Impact: CLIP enables powerful zero-shot capabilities. For example, given an image, it can classify it into arbitrary categories by comparing the image's embedding to the embeddings of various text descriptions (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog"). It revolutionized image search, content moderation, and few-shot learning.

-

Generative Models (DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney):

- Mechanism: These models leverage the power of diffusion models, which learn to gradually denoise a random noise image into a coherent image, conditioned on a text prompt. The text prompt is typically encoded into an embedding space using a text encoder (often derived from CLIP or similar models).

- Impact: They have democratized creative content generation, allowing users to generate high-quality, diverse images from simple text descriptions. This represents a monumental leap in image synthesis and editing, opening up new possibilities for art, design, and media.

-

Vision-Language Models for Few-Shot Learning (Flamingo, BLIP-2):

- Mechanism: These models aim to combine the strengths of large language models (LLMs) with vision encoders to enable efficient few-shot learning across a wide range of vision and language tasks. They often use techniques like "perceiver resampler" or "Q-Former" to bridge the gap between the vision and language modalities, allowing the LLM to "see" and understand visual input.

- Impact: They can perform tasks like visual question answering, image captioning, and visual dialogue with remarkable proficiency, even with minimal task-specific examples.

Practical Applications and Emerging Trends

The impact of foundation models in computer vision is already being felt across numerous industries and applications:

- Robust Object Recognition & Detection: ViT-based detectors like DETR (DEtection TRansformer) and Swin Transformer-based architectures are achieving state-of-the-art performance in object detection and instance segmentation. Their global context awareness can lead to more robust detection in complex scenes.

- Semantic Segmentation & Instance Segmentation: Swin Transformers and similar hierarchical ViTs have significantly advanced dense prediction tasks, crucial for autonomous driving, medical imaging, and robotics.

- Zero-Shot & Few-Shot Learning: Models like CLIP are transforming how we deploy AI. Instead of retraining for every new category, a model can classify unseen objects by simply providing text descriptions, making AI systems more adaptable and scalable.

- Image Generation & Editing: The explosion of text-to-image models has revolutionized creative industries, allowing rapid prototyping, personalized content creation, and novel artistic expression. These models are also being adapted for image editing tasks, such as inpainting, outpainting, and style transfer.

- Medical Imaging: Foundation models offer the promise of more robust and generalizable diagnostic tools. Pre-trained on vast amounts of natural images, they can be fine-tuned with smaller medical datasets to assist in tasks like tumor detection, disease classification, and organ segmentation, potentially reducing the need for extensive manual annotation by radiologists.

- Autonomous Driving: Enhanced perception systems leveraging these models can lead to more accurate and reliable object detection, lane keeping, scene understanding, and prediction of pedestrian and vehicle behavior, improving safety and efficiency.

- Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis: Analyzing satellite imagery for urban planning, environmental monitoring, and disaster response can benefit immensely from foundation models that can quickly identify features, changes, and anomalies across vast geographical areas.

- Efficiency and Deployment: While these models are large, ongoing research focuses on making them more efficient for inference. Techniques like quantization, pruning, distillation, and specialized hardware accelerators are crucial for deploying these powerful models on edge devices or in real-time applications.

Conclusion: A Foundation for the Future

The era of foundation models in computer vision marks a pivotal moment in AI development. The shift from CNNs to Transformers, coupled with the power of self-supervised learning and multi-modal integration, has unlocked unprecedented capabilities. These models are not just achieving higher benchmarks; they are fundamentally changing how we approach problem-solving in computer vision, enabling more generalizable, adaptable, and intelligent systems.

For AI practitioners, understanding these architectures, their training methodologies, and their strengths is paramount. It empowers them to leverage powerful pre-trained models, significantly reducing development time and data requirements for specific tasks. For enthusiasts, it opens a window into the cutting edge of AI, offering a glimpse into a future where machines can "see," understand, and interact with the visual world in increasingly sophisticated ways.

As research continues at a blistering pace, we can expect even more innovative architectures, more efficient training paradigms, and an even broader array of practical applications. The foundation has been laid, and the future of computer vision looks more exciting and impactful than ever before.