The Vision Revolution: How Transformers Are Reshaping Computer Vision

Discover how the Transformer architecture, initially a game-changer in NLP, is now fundamentally altering the landscape of computer vision. Learn about the rise of Vision Transformers (ViT) and their profound impact.

The Vision Revolution: How Transformers Are Reshaping Computer Vision

For decades, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) reigned supreme in computer vision. Their hierarchical structure, built-in inductive biases like locality and translation equivariance, and remarkable ability to extract features from images made them the undisputed champions for tasks ranging from image classification to object detection. Then, a new contender emerged from the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP): the Transformer.

Initially designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks, the Transformer architecture, with its powerful self-attention mechanism, revolutionized NLP. It wasn't long before researchers wondered if this paradigm-shifting architecture could be adapted for images. The answer came in 2020 with the introduction of the Vision Transformer (ViT), and since then, the landscape of computer vision has been irrevocably changed. ViTs are not just another incremental improvement; they represent a fundamental shift, paving the way for truly general-purpose visual AI models – often referred to as "foundation models" – that can understand and reason about the visual world with unprecedented flexibility and power.

This post will delve into the fascinating world of Vision Transformers, exploring their core mechanics, why they're so impactful, their rapid evolution, and the practical implications for anyone working with or interested in AI.

From Words to Pixels: The Core Idea of Vision Transformers

At its heart, a Transformer processes sequences. The ingenious leap for ViTs was to realize that an image, despite its 2D nature, could be treated as a sequence. But how?

The Transformer Architecture: A Quick Recap

Before diving into ViTs, let's briefly recall the core components of a Transformer encoder, which is what ViTs primarily leverage:

- Input Embeddings: Input tokens (words in NLP) are converted into dense vector representations.

- Positional Embeddings: Since self-attention is permutation-invariant (it doesn't inherently understand order), positional information is added to the embeddings to preserve sequence order.

- Multi-Head Self-Attention: This is the magic ingredient. It allows each token in the sequence to "attend" to every other token, calculating a weighted sum of their features. This mechanism captures long-range dependencies and global context. "Multi-head" means this process is done in parallel multiple times with different learned linear projections, allowing the model to focus on different aspects of relationships.

- Feed-Forward Networks (FFN): After attention, each token's representation is passed through a simple, position-wise feed-forward neural network.

- Layer Normalization & Residual Connections: These techniques are used throughout the network to stabilize training and improve gradient flow.

Adapting to Vision: The ViT Blueprint

The key innovation of the original Vision Transformer paper ("An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale" by Dosovitskiy et al.) was to translate these NLP concepts to the visual domain:

- Image Patching: An image is first divided into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches. For example, a 224x224 pixel image might be divided into 16x16 pixel patches. If the image is RGB (3 channels), each 16x16 patch becomes a 16x16x3 tensor.

- Example: A 224x224 image divided into 16x16 patches yields (224/16) * (224/16) = 14 * 14 = 196 patches.

- Linear Embedding (Patch Projection): Each 16x16x3 patch is then flattened into a 1D vector (16*16*3 = 768 dimensions). This flattened vector is then linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space, typically 768 or 1024 dimensions, similar to word embeddings in NLP.

- Learnable

[CLS]Token: Similar to BERT, a special learnable classification token ([CLS]) embedding is prepended to the sequence of patch embeddings. The final state of this[CLS]token after passing through the Transformer encoder is used for classification. - Positional Embeddings: To retain the spatial information lost by flattening and sequencing the patches, learnable 1D positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings. These embeddings encode the original position of each patch in the image grid.

- Transformer Encoder Stack: The sequence of

[CLS]token plus patch embeddings is then fed into a standard Transformer encoder, consisting of multiple layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. - Classification Head: Finally, the output embedding corresponding to the

[CLS]token from the last Transformer layer is passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) head for classification.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.n_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.patch_dim = in_channels * patch_size * patch_size

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

# x: (batch_size, in_channels, img_size, img_size)

x = self.proj(x) # (batch_size, embed_dim, n_patches_sqrt, n_patches_sqrt)

x = x.flatten(2) # (batch_size, embed_dim, n_patches)

x = x.transpose(1, 2) # (batch_size, n_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Simplified Transformer Encoder Block

class TransformerEncoderBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embed_dim, num_heads, mlp_ratio=4., dropout=0.):

super().__init__()

self.norm1 = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.attn = nn.MultiheadAttention(embed_dim, num_heads, dropout=dropout, batch_first=True)

self.norm2 = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.mlp = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(embed_dim, int(embed_dim * mlp_ratio)),

nn.GELU(),

nn.Dropout(dropout),

nn.Linear(int(embed_dim * mlp_ratio), embed_dim),

nn.Dropout(dropout)

)

def forward(self, x):

x = x + self.attn(self.norm1(x), self.norm1(x), self.norm1(x))[0]

x = x + self.mlp(self.norm2(x))

return x

# Conceptual ViT (simplified)

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size=224, patch_size=16, in_channels=3, num_classes=1000,

embed_dim=768, depth=12, num_heads=12, mlp_ratio=4., dropout=0.):

super().__init__()

self.patch_embed = PatchEmbedding(img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim)

self.cls_token = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, 1, embed_dim))

self.pos_embed = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, 1 + self.patch_embed.n_patches, embed_dim))

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.blocks = nn.ModuleList([

TransformerEncoderBlock(embed_dim, num_heads, mlp_ratio, dropout)

for _ in range(depth)

])

self.norm = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.head = nn.Linear(embed_dim, num_classes)

def forward(self, x):

batch_size = x.shape[0]

x = self.patch_embed(x) # (batch_size, n_patches, embed_dim)

cls_tokens = self.cls_token.expand(batch_size, -1, -1) # (batch_size, 1, embed_dim)

x = torch.cat((cls_tokens, x), dim=1) # (batch_size, 1 + n_patches, embed_dim)

x = x + self.pos_embed # Add positional embeddings

x = self.dropout(x)

for block in self.blocks:

x = block(x)

x = self.norm(x)

cls_output = x[:, 0] # Take the output of the CLS token

logits = self.head(cls_output)

return logits

# Example usage:

# model = VisionTransformer()

# dummy_input = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224)

# output = model(dummy_input)

# print(output.shape) # torch.Size([1, 1000])

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.n_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.patch_dim = in_channels * patch_size * patch_size

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

# x: (batch_size, in_channels, img_size, img_size)

x = self.proj(x) # (batch_size, embed_dim, n_patches_sqrt, n_patches_sqrt)

x = x.flatten(2) # (batch_size, embed_dim, n_patches)

x = x.transpose(1, 2) # (batch_size, n_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Simplified Transformer Encoder Block

class TransformerEncoderBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embed_dim, num_heads, mlp_ratio=4., dropout=0.):

super().__init__()

self.norm1 = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.attn = nn.MultiheadAttention(embed_dim, num_heads, dropout=dropout, batch_first=True)

self.norm2 = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.mlp = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(embed_dim, int(embed_dim * mlp_ratio)),

nn.GELU(),

nn.Dropout(dropout),

nn.Linear(int(embed_dim * mlp_ratio), embed_dim),

nn.Dropout(dropout)

)

def forward(self, x):

x = x + self.attn(self.norm1(x), self.norm1(x), self.norm1(x))[0]

x = x + self.mlp(self.norm2(x))

return x

# Conceptual ViT (simplified)

class VisionTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size=224, patch_size=16, in_channels=3, num_classes=1000,

embed_dim=768, depth=12, num_heads=12, mlp_ratio=4., dropout=0.):

super().__init__()

self.patch_embed = PatchEmbedding(img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim)

self.cls_token = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, 1, embed_dim))

self.pos_embed = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, 1 + self.patch_embed.n_patches, embed_dim))

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.blocks = nn.ModuleList([

TransformerEncoderBlock(embed_dim, num_heads, mlp_ratio, dropout)

for _ in range(depth)

])

self.norm = nn.LayerNorm(embed_dim)

self.head = nn.Linear(embed_dim, num_classes)

def forward(self, x):

batch_size = x.shape[0]

x = self.patch_embed(x) # (batch_size, n_patches, embed_dim)

cls_tokens = self.cls_token.expand(batch_size, -1, -1) # (batch_size, 1, embed_dim)

x = torch.cat((cls_tokens, x), dim=1) # (batch_size, 1 + n_patches, embed_dim)

x = x + self.pos_embed # Add positional embeddings

x = self.dropout(x)

for block in self.blocks:

x = block(x)

x = self.norm(x)

cls_output = x[:, 0] # Take the output of the CLS token

logits = self.head(cls_output)

return logits

# Example usage:

# model = VisionTransformer()

# dummy_input = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224)

# output = model(dummy_input)

# print(output.shape) # torch.Size([1, 1000])

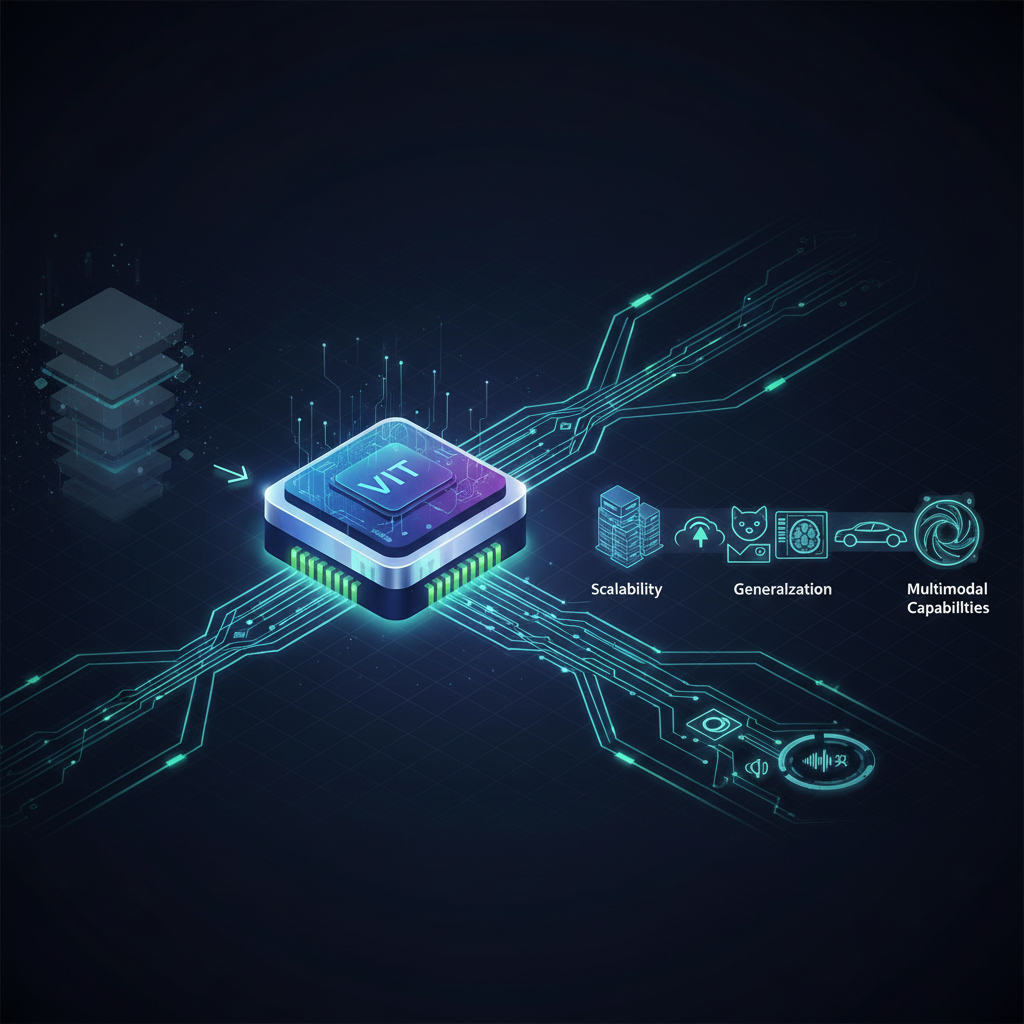

Why ViTs are a Game Changer: Advantages over CNNs

The shift to Transformers in vision wasn't just about novelty; it brought significant advantages:

- Global Receptive Field from Layer One: CNNs build up a global understanding of an image gradually through many layers of small convolutional filters and pooling operations. ViTs, through self-attention, allow every patch to directly interact with every other patch from the very first layer. This provides a truly global receptive field, enabling the model to capture long-range dependencies and contextual information immediately.

- Reduced Inductive Biases: CNNs are designed with strong inductive biases:

- Locality: Pixels close together are more related.

- Translation Equivariance: If an object moves, its features also move spatially. These biases are beneficial for smaller datasets as they encode prior knowledge. However, they can also limit a CNN's ability to learn more flexible and general patterns from massive datasets. ViTs are more "data-hungry" but, given enough data, can learn these patterns from scratch, leading to more generalizable representations.

- Scalability with Data: This is perhaps the most profound advantage. ViTs, especially larger variants, scale remarkably well with the amount of pre-training data. When pre-trained on massive datasets (like JFT-300M, a proprietary dataset with 300 million images), ViTs consistently outperform state-of-the-art CNNs. The more data, the better they perform, often without saturation.

- Interpretability through Attention Maps: The attention weights within the Transformer layers can be visualized. These "attention maps" show which parts of the image the model is focusing on when processing a particular patch or making a prediction, offering insights into its decision-making process.

The Rapid Evolution of Vision Transformers

The initial ViT paper opened the floodgates, and research in this area has exploded. Here are some of the most significant developments and emerging trends:

- Data-Efficient ViTs (DeiT): The original ViT was notoriously data-hungry, requiring huge datasets to surpass CNNs. DeiT (Data-efficient Image Transformers) addressed this by introducing a token-based knowledge distillation strategy. It uses a CNN as a teacher to guide the ViT's training, allowing ViTs to achieve competitive performance even on smaller datasets like ImageNet-1K, making them more accessible.

- Hierarchical ViTs (e.g., Swin Transformer): A limitation of vanilla ViTs for dense prediction tasks (like object detection and segmentation) was their fixed-resolution patches and lack of hierarchical feature maps, which CNNs naturally provide. The Swin Transformer (Shifted Window Transformer) revolutionized this by:

- Hierarchical Feature Maps: Starting with small patches and progressively merging them in deeper layers, creating multi-scale representations akin to feature pyramids in CNNs.

- Shifted Window Attention: Instead of global attention, Swin uses attention within local "windows" and then shifts these windows in subsequent layers. This reduces computational cost while still allowing for cross-window interaction. Swin Transformers have achieved state-of-the-art results across a wide range of vision tasks, often surpassing both CNNs and previous ViT variants.

- Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, MAE (Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners) introduced a highly effective self-supervised pre-training strategy for ViTs. A large portion of image patches (e.g., 75%) is masked out, and the ViT is trained to reconstruct the missing pixel values. This forces the model to learn rich, semantic representations of the image content. MAE has proven incredibly powerful for pre-training on vast amounts of unlabeled image data, significantly reducing the need for expensive labeled datasets.

- Efficient ViTs: The computational cost of global self-attention (quadratic with sequence length) is a major bottleneck for high-resolution images. Research is actively exploring ways to make ViTs more efficient:

- Sparse Attention: Only attending to a subset of patches.

- Linear Attention: Approximating attention with linear operations.

- Smaller Patch Sizes/Models: Optimizing model architecture and parameters.

- Knowledge Distillation: Transferring knowledge from large ViTs to smaller, more efficient ones.

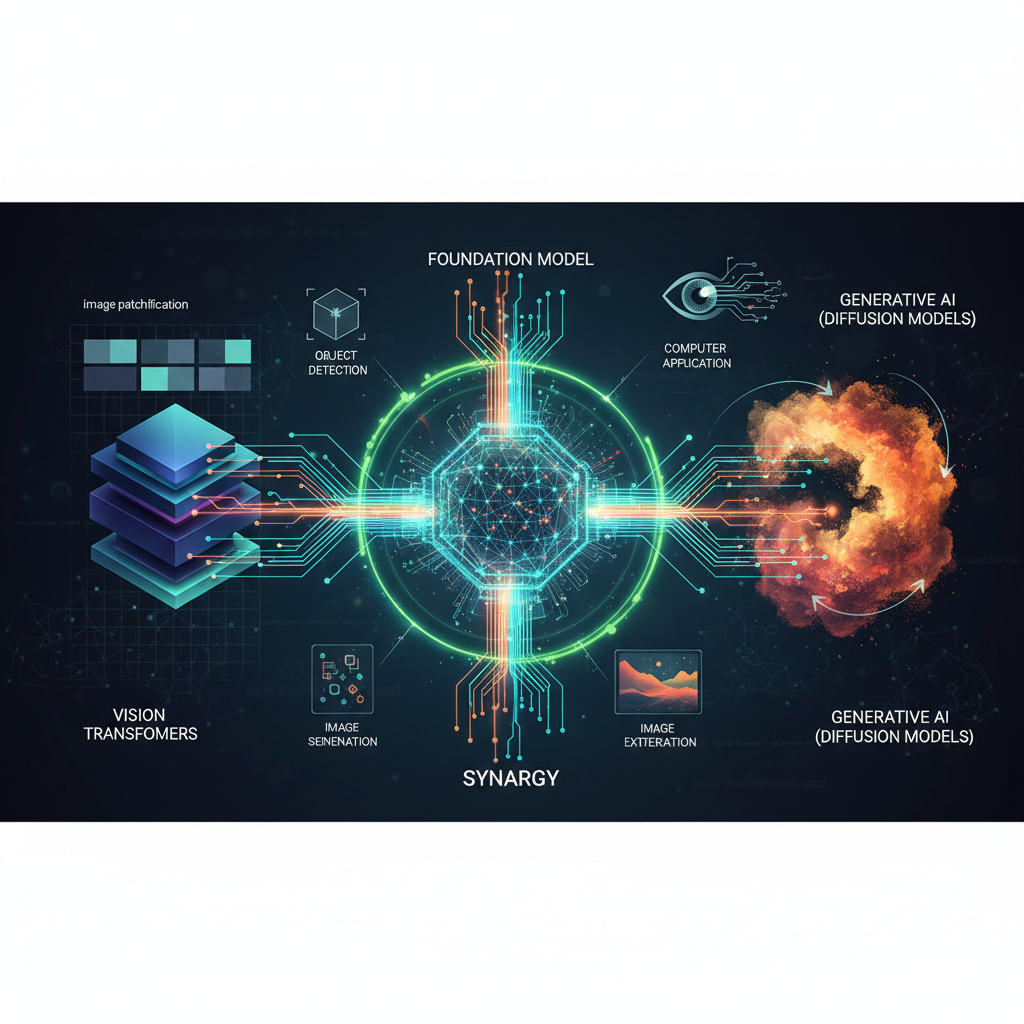

- Multimodal ViTs and Vision-Language Foundation Models: This is where ViTs truly shine in the context of "foundation models." Models like CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) and ALIGN leverage ViTs to learn powerful joint representations of images and text. By training on massive datasets of image-text pairs, these models learn to associate visual concepts with linguistic descriptions. This enables:

- Zero-Shot Learning: Classifying images into categories they've never seen during training, simply by providing text descriptions of those categories.

- Image Generation: Models like DALL-E 2 and Stable Diffusion use Transformers (often ViT-like components) to generate high-quality images from text prompts, demonstrating a deep understanding of visual concepts and their textual counterparts.

- Video Transformers: Extending the patch-based approach to video, treating spatio-temporal patches (3D cubes of pixels across time) as input tokens. These models are pushing the boundaries of video understanding, action recognition, and temporal reasoning.

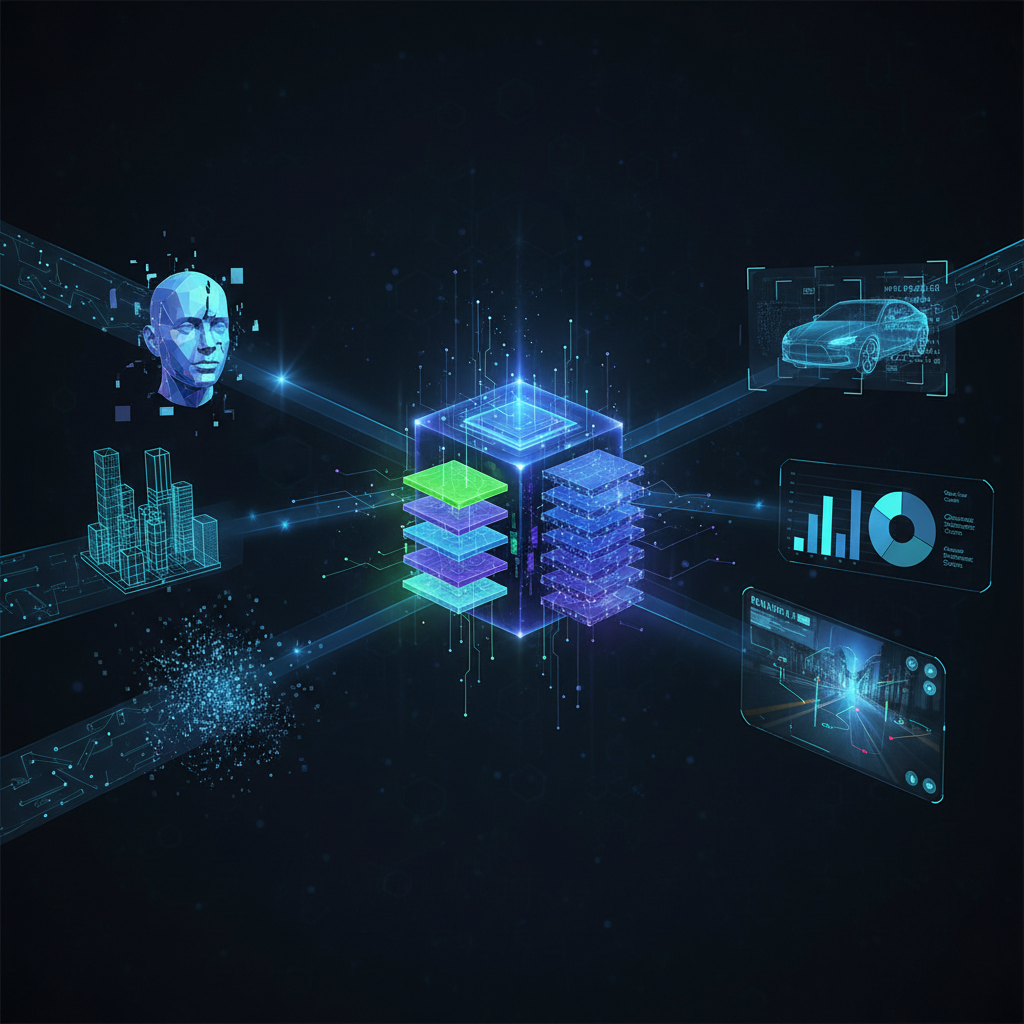

Practical Applications and Value for Practitioners

The advancements in ViTs translate directly into powerful tools and capabilities for AI practitioners and enthusiasts:

- State-of-the-Art Image Classification: Whether it's medical image analysis, industrial quality control, or content moderation, ViTs offer superior accuracy, especially when large pre-trained models are fine-tuned.

- Advanced Object Detection and Segmentation: Hierarchical ViTs like Swin Transformer are now the backbone of leading models for detecting objects and segmenting images with high precision, crucial for autonomous driving, robotics, and augmented reality.

- Leveraging Unlabeled Data: Self-supervised pre-training methods like MAE allow organizations with vast amounts of unlabeled image data (e.g., surveillance footage, internal photo archives) to pre-train powerful visual models without the prohibitive cost of manual annotation.

- Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Learning: For new applications where labeled data is scarce, foundation models like CLIP enable rapid deployment. Imagine classifying rare animal species or detecting new manufacturing defects with just a few examples or even just text descriptions.

- Medical Imaging Breakthroughs: ViTs' ability to capture global context and learn robust features makes them ideal for tasks like early disease detection from X-rays or MRIs, tumor segmentation, and pathology analysis.

- Remote Sensing and Geospatial AI: Analyzing satellite imagery for environmental monitoring, urban planning, disaster response, and agricultural yield prediction benefits from ViTs' ability to process large-scale visual data.

- Generative AI: For creatives, developers, and businesses, the power of text-to-image generation from models like DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney (all heavily relying on Transformers) is transformative for content creation, design, and prototyping.

- Enhanced Robustness: ViTs often exhibit better robustness to adversarial attacks and improved generalization to out-of-distribution data compared to CNNs, making them more reliable for real-world deployment in critical applications.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their immense success, ViTs are not without their challenges, and these areas represent active research frontiers:

- Computational Cost: Vanilla ViTs can be computationally expensive and memory-intensive, especially for very high-resolution images or real-time applications on edge devices. Efficient ViT designs are crucial for broader adoption.

- Data Requirements: While self-supervised methods help, training the largest ViTs from scratch still demands immense datasets and computational resources, limiting access for smaller research groups or companies.

- Interpretability Beyond Attention: While attention maps provide some insight, a deeper, more mechanistic understanding of why Transformers are so effective in vision and what specific features they learn is still an open question.

- Theoretical Foundations: Further theoretical work is needed to fully understand the inductive biases (or lack thereof) of ViTs and their implications for learning and generalization.

- Deployment on Edge Devices: Adapting these large, powerful models for deployment on resource-constrained devices (e.g., smartphones, embedded systems) remains a significant hurdle. Model compression, quantization, and specialized hardware will be key.

Conclusion

The advent of Vision Transformers marks a pivotal moment in computer vision, akin to the Transformer's impact on NLP. By treating images as sequences of patches and leveraging the power of self-attention, ViTs have shattered long-held assumptions about the necessity of convolutions for visual understanding. Their remarkable scalability, ability to learn generalizable representations from massive datasets, and adaptability to a multitude of tasks position them as the cornerstone of the next generation of visual AI foundation models.

For AI practitioners, understanding the nuances of ViTs, their diverse variants like Swin and MAE, and their integration into multimodal systems is no longer optional – it's essential for staying at the forefront of innovation. For enthusiasts, the sheer power and versatility of these models, particularly in generative AI and zero-shot learning, offer a glimpse into a future where AI can truly "see" and understand the world around us with unprecedented depth. The vision revolution is here, and it's being led by Transformers.