Foundation Models & Vision Transformers: Revolutionizing Computer Vision

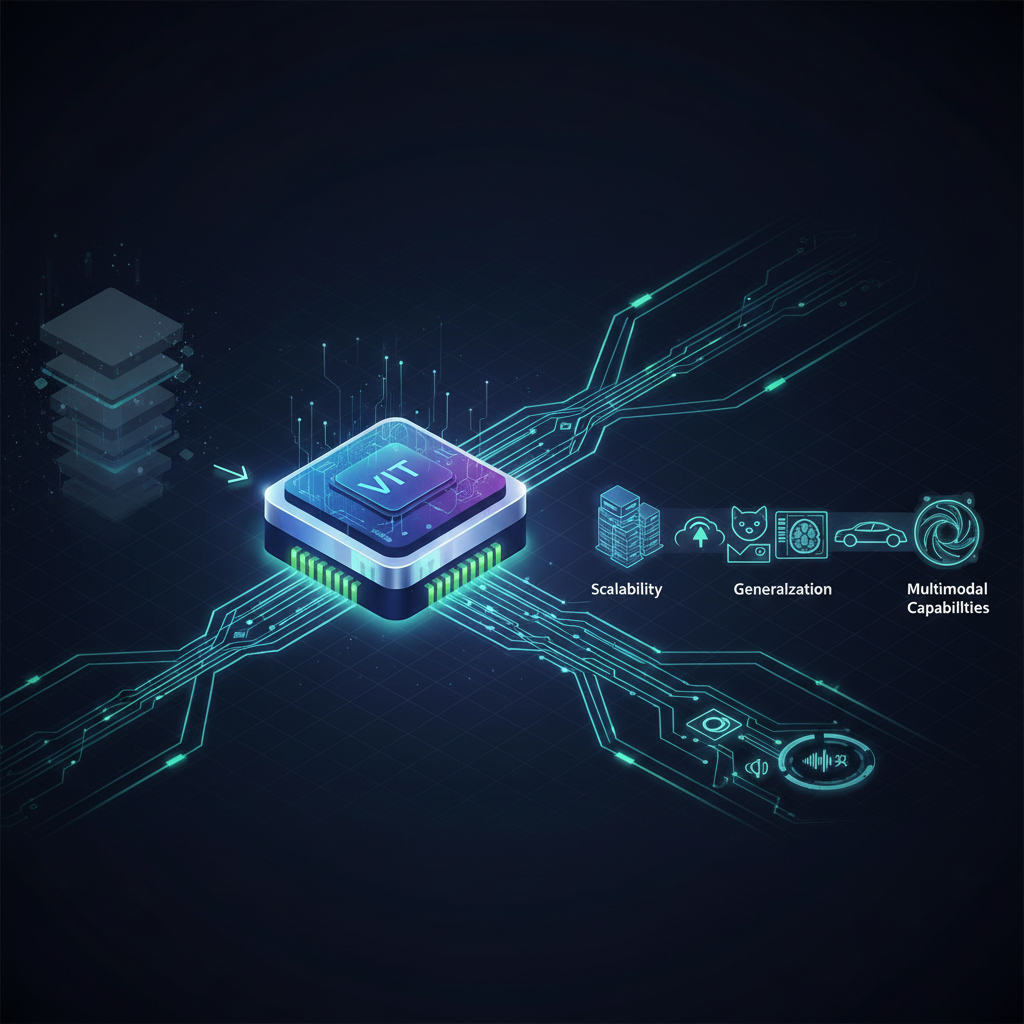

Explore the paradigm shift in computer vision from CNNs to powerful foundation models like Vision Transformers (ViTs). Discover how this new era offers unprecedented scalability, generalization, and multimodal capabilities, fundamentally changing machine perception.

The Dawn of a New Era: Foundation Models Revolutionizing Computer Vision

For decades, the field of computer vision was largely synonymous with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). These ingenious architectures, inspired by the human visual cortex, propelled object recognition, image classification, and segmentation to unprecedented heights. From AlexNet to ResNet, CNNs reigned supreme, meticulously crafting hierarchical features through layers of convolutions and pooling. However, a seismic shift has occurred, mirroring the revolution seen in Natural Language Processing (NLP) with the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs). We are now firmly in the era of Foundation Models for Computer Vision, spearheaded by Vision Transformers (ViTs) and their powerful descendants. This paradigm shift is not merely an incremental improvement; it's a fundamental reimagining of how machines perceive and understand the visual world, offering scalability, generalization, and multimodal capabilities that were once the stuff of science fiction.

Why This Transformation Matters: A Paradigm Shift in Visual AI

The transition to foundation models in computer vision is driven by several compelling factors that make this topic incredibly timely and impactful:

- Beyond CNNs: A New Architectural Blueprint: ViTs broke free from the inductive biases of CNNs (locality and translation equivariance) by treating images as sequences of patches, processed by the powerful self-attention mechanism of the Transformer architecture. This allows for global context understanding from the outset, a departure from CNNs' local-to-global feature aggregation.

- Unprecedented Scalability and Generalization: Foundation models are designed to learn broad, transferable representations from vast, diverse datasets. This "pre-train then fine-tune" paradigm means a single, massive model can be adapted to numerous downstream tasks with minimal task-specific data, drastically reducing development time and data annotation costs.

- The Power of Unlabeled Data: Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): The success of foundation models hinges on their ability to learn from unlabeled data. SSL techniques enable models to extract rich visual semantics without human supervision, overcoming the bottleneck of expensive and time-consuming data labeling.

- Bridging Vision and Language: Multimodal Intelligence: Perhaps one of the most exciting aspects is the convergence of vision and language. Models like CLIP and DALL-E demonstrate how foundation models can seamlessly integrate these modalities, leading to capabilities like zero-shot image classification, text-to-image generation, and semantic image search.

- Democratization of State-of-the-Art AI: Pre-trained foundation models are increasingly available through platforms like Hugging Face, allowing practitioners and enthusiasts to leverage cutting-edge performance without needing access to supercomputing resources for training from scratch.

Understanding these foundational shifts is crucial for anyone looking to build the next generation of AI applications, from autonomous systems to creative content generation.

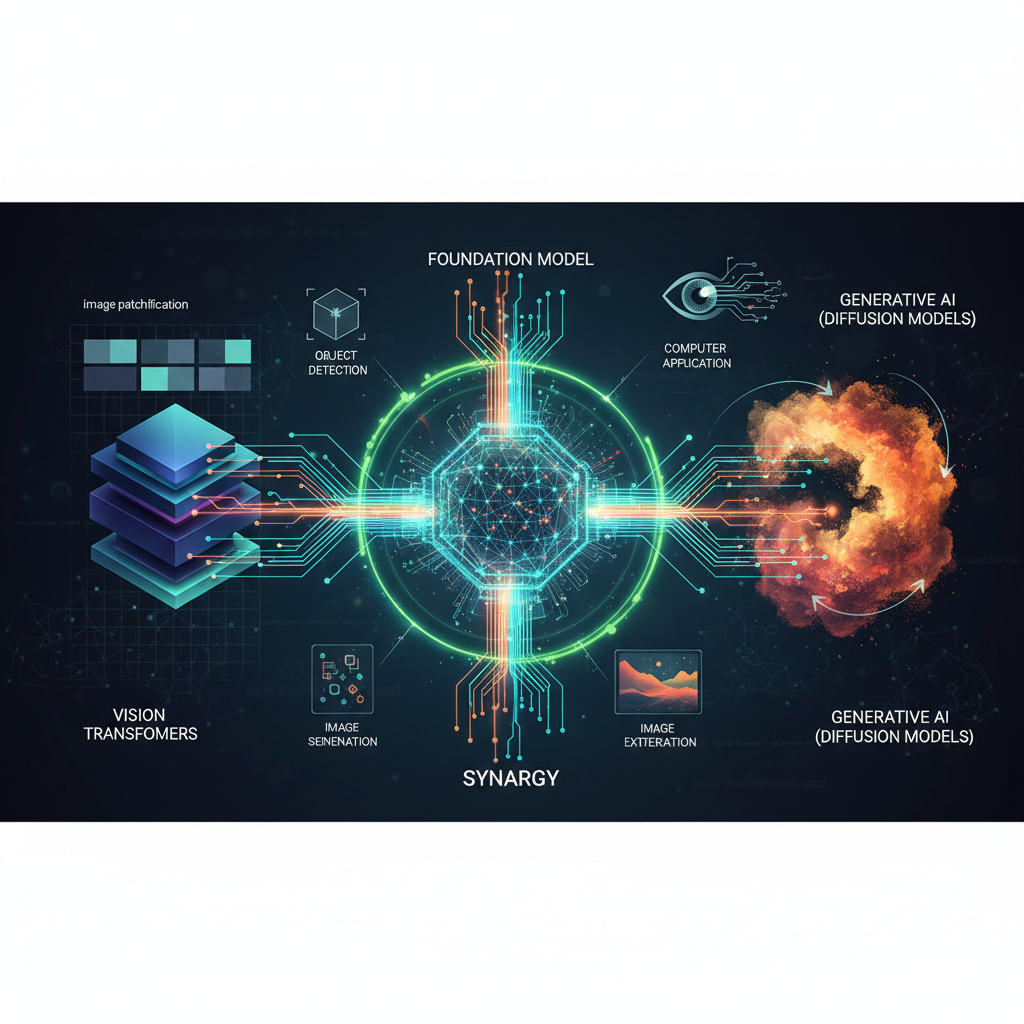

The Architectural Evolution: From ViT to Modern Vision Foundation Models

The journey began with a bold idea: apply the Transformer, a model designed for sequential data like text, to images.

Vision Transformers (ViTs): The Genesis

The original Vision Transformer (ViT), introduced by Google in 2020, was a landmark paper. It demonstrated that a pure Transformer encoder, applied directly to sequences of image patches, could achieve state-of-the-art performance on image classification tasks, especially when pre-trained on large datasets.

How ViT Works (Simplified):

- Image Patching: An input image is divided into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels).

- Linear Embedding: Each patch is flattened and linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space.

- Positional Embeddings: To retain spatial information (which is lost when flattening patches), learnable positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings.

- Class Token: A special "class token" embedding is prepended to the sequence, similar to BERT's

[CLS]token. This token's final output state will serve as the image's overall representation for classification. - Transformer Encoder: The sequence of patch embeddings (plus class token and positional embeddings) is fed into a standard Transformer encoder, consisting of multiple layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks.

- Classification Head: The output of the class token from the final Transformer layer is passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) head for classification.

# Conceptual Python-like pseudocode for ViT patch embedding

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

self.pos_embed = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, self.num_patches + 1, embed_dim)) # +1 for class token

def forward(self, x):

B, C, H, W = x.shape

# Project patches to embed_dim

x = self.proj(x).flatten(2).transpose(1, 2) # (B, num_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Example usage

# img = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224) # Batch, Channels, Height, Width

# patch_embed_layer = PatchEmbedding(img_size=224, patch_size=16, in_channels=3, embed_dim=768)

# patch_embeddings = patch_embed_layer(img)

# print(patch_embeddings.shape) # Expected: torch.Size([1, 196, 768]) (for 224/16=14 -> 14*14=196 patches)

# Conceptual Python-like pseudocode for ViT patch embedding

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

self.pos_embed = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(1, self.num_patches + 1, embed_dim)) # +1 for class token

def forward(self, x):

B, C, H, W = x.shape

# Project patches to embed_dim

x = self.proj(x).flatten(2).transpose(1, 2) # (B, num_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Example usage

# img = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224) # Batch, Channels, Height, Width

# patch_embed_layer = PatchEmbedding(img_size=224, patch_size=16, in_channels=3, embed_dim=768)

# patch_embeddings = patch_embed_layer(img)

# print(patch_embeddings.shape) # Expected: torch.Size([1, 196, 768]) (for 224/16=14 -> 14*14=196 patches)

The initial ViT paper highlighted that while ViTs performed exceptionally well with massive datasets (like JFT-300M), they struggled with smaller datasets compared to CNNs, leading to the development of Data-efficient Image Transformers (DeiT). DeiT showed that ViTs could be competitive even with less data by employing a distillation strategy, where a ViT learns from a CNN teacher.

Swin Transformer: Bringing Hierarchy and Efficiency

A key limitation of the original ViT was its quadratic complexity with respect to the number of patches due to global self-attention. This made it computationally expensive for high-resolution images or dense prediction tasks like segmentation, where many small patches are needed. The Swin Transformer addressed this by introducing:

- Hierarchical Feature Maps: Similar to CNNs, Swin builds hierarchical representations by merging image patches in deeper layers, creating progressively smaller feature maps.

- Shifted Window-based Self-Attention: Instead of global attention, Swin computes self-attention within non-overlapping local windows. To allow for cross-window connections, the windows are shifted between successive layers. This significantly reduces computational cost while retaining global context.

Swin Transformer quickly became a backbone of choice for various vision tasks, demonstrating that Transformers could indeed be efficient and effective for dense prediction.

Masked Autoencoders (MAE): The Power of Reconstruction

Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, Masked Autoencoders (MAE) introduced a highly effective self-supervised pre-training strategy for ViTs. MAE randomly masks a large portion (e.g., 75%) of image patches and then trains the ViT encoder to reconstruct the missing pixel values of these masked patches.

Key Insights of MAE:

- Asymmetric Encoder-Decoder: The encoder only processes the visible patches, making it very efficient. A lightweight decoder then reconstructs the full image from the encoder's output and the masked tokens.

- High Masking Ratio: Unlike NLP, where masking too much can make the task trivial, MAE benefits from a very high masking ratio, forcing the model to learn deep semantic understanding rather than just local pixel correlations.

- Remarkable Transfer Learning: Models pre-trained with MAE achieve excellent performance on various downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning.

MAE represents a significant step towards truly general-purpose visual representation learning, moving away from contrastive learning's reliance on augmentations.

ConvNeXt: A CNN's Comeback, Influenced by Transformers

In a fascinating turn, the ConvNeXt architecture showed that modern CNNs, when designed with principles learned from ViTs, can achieve competitive or even superior performance. ConvNeXt incorporated elements like:

- Larger Kernel Sizes: Moving from small 3x3 kernels to larger ones (e.g., 7x7), similar to the effective receptive field of ViT patches.

- Inverted Bottleneck and Layer Scaling: Borrowing from architectures like MobileNetV2 and EfficientNet.

- Replacing ReLU with GELU: A common activation function in Transformers.

- Fewer Activation Functions and Normalization Layers: Streamlining the architecture.

ConvNeXt blurs the lines between CNNs and Transformers, suggesting that the architectural innovations of ViTs can inform and improve traditional CNNs, leading to a convergence of ideas.

The Unsung Hero: Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)

The ability of foundation models to learn from vast amounts of unlabeled data is their superpower, and Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) is the engine behind it. SSL methods create supervisory signals from the data itself, allowing models to learn rich representations without explicit human labels.

Key SSL Approaches:

- Contrastive Learning (e.g., SimCLR, MoCo): These methods train models to bring "positive pairs" (different augmented views of the same image) closer in the embedding space while pushing "negative pairs" (different images) further apart. This forces the model to learn features that are invariant to various augmentations but discriminative between different images.

- Masked Image Modeling (MIM) (e.g., MAE, BEiT): As discussed with MAE, MIM involves masking parts of the input and training the model to reconstruct them. This has become a dominant strategy for ViTs due to its simplicity and effectiveness.

- DINO/DINOv2: Self-supervised learning with Vision Transformers that learns dense features and can perform zero-shot segmentation without explicit pixel-level labels. DINO uses a "knowledge distillation" approach where a student network learns from a teacher network (which is an exponential moving average of the student), without labels. It encourages the student to produce similar outputs to the teacher for different views of the same image, while also using a "centering" and "sharpening" trick to prevent mode collapse.

SSL is critical because it unlocks the potential of the internet's vast ocean of unlabeled images, circumventing the bottleneck of human annotation which is often expensive, slow, and prone to bias.

Beyond Pixels: Multimodal Foundation Models (VLMs)

The ultimate goal of AI is often seen as achieving human-like understanding, which inherently involves multiple senses and modalities. Vision-Language Models (VLMs) are a significant step in this direction, integrating visual and textual information.

CLIP: Connecting Images and Text Semantically

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) from OpenAI was a game-changer. It learns to associate images with natural language descriptions by training on a massive dataset of image-text pairs collected from the internet. CLIP doesn't predict captions; instead, it learns a shared embedding space where semantically similar image and text embeddings are close together.

Impact of CLIP:

- Zero-Shot Classification: CLIP can classify images into categories it has never seen during training. You simply provide text descriptions of the categories (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a picture of a dog"), and CLIP will find the image embedding closest to the text embedding.

- Image Retrieval: Search for images using natural language queries.

- Image-to-Text Generation: While not directly generating text, CLIP's embeddings can be used in conjunction with text decoders.

Generative Models: DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney

These models represent the pinnacle of multimodal creativity. They take text prompts and generate highly realistic, diverse, and often artistic images.

- Diffusion Models: The underlying technology for many of these, including Stable Diffusion, involves iteratively denoising a noisy image based on a text prompt. They have shown incredible fidelity and control compared to previous generative adversarial networks (GANs).

- Integration with VLMs: These generative models often leverage VLMs like CLIP to understand the semantic content of the text prompt and guide the image generation process.

Models like Flamingo and CoCa further integrate vision and language, enabling few-shot learning for various visual tasks by leveraging textual instructions, pushing towards more general-purpose visual assistants.

Practical Applications for Practitioners and Enthusiasts

The theoretical advancements translate directly into powerful tools and capabilities for real-world AI applications.

-

State-of-the-Art Image Classification and Object Detection:

- Example: Instead of training a CNN from scratch for a custom classification task (e.g., identifying different types of industrial defects), you can fine-tune a pre-trained ViT (e.g.,

google/vit-base-patch16-224from Hugging Face Transformers) on your specific dataset. This typically requires significantly less labeled data and computational resources, and often yields superior performance. - Code Snippet (Conceptual Fine-tuning with Hugging Face Transformers):

python

from transformers import ViTForImageClassification, ViTImageProcessor from datasets import load_dataset import torch # Load a pre-trained ViT model and its processor model_name = "google/vit-base-patch16-224" processor = ViTImageProcessor.from_pretrained(model_name) model = ViTForImageClassification.from_pretrained(model_name, num_labels=num_your_classes) # Assuming 'your_dataset' is loaded and processed # Example: train_dataset, eval_dataset = load_your_custom_dataset() # Define training arguments and Trainer (using Hugging Face Trainer API) # trainer = Trainer(model=model, args=training_args, train_dataset=train_dataset, ...) # trainer.train()from transformers import ViTForImageClassification, ViTImageProcessor from datasets import load_dataset import torch # Load a pre-trained ViT model and its processor model_name = "google/vit-base-patch16-224" processor = ViTImageProcessor.from_pretrained(model_name) model = ViTForImageClassification.from_pretrained(model_name, num_labels=num_your_classes) # Assuming 'your_dataset' is loaded and processed # Example: train_dataset, eval_dataset = load_your_custom_dataset() # Define training arguments and Trainer (using Hugging Face Trainer API) # trainer = Trainer(model=model, args=training_args, train_dataset=train_dataset, ...) # trainer.train()

- Example: Instead of training a CNN from scratch for a custom classification task (e.g., identifying different types of industrial defects), you can fine-tune a pre-trained ViT (e.g.,

-

Zero-Shot Learning for Dynamic Classification:

- Example: Imagine an e-commerce platform that needs to categorize newly uploaded products, some of which might belong to categories not present in the original training data. Using CLIP, you can classify an image of a "vintage leather handbag" even if your model was never explicitly trained on that category. You just provide the text description "vintage leather handbag" alongside other category descriptions, and CLIP will find the best match.

- Code Snippet (Conceptual CLIP Zero-Shot Classification):

python

from transformers import CLIPProcessor, CLIPModel from PIL import Image # Load CLIP model and processor model = CLIPModel.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32") processor = CLIPProcessor.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32") # Load your image image = Image.open("path/to/your/image.jpg") # Define candidate labels candidate_labels = ["a photo of a cat", "a photo of a dog", "a photo of a car"] # Process inputs inputs = processor(text=candidate_labels, images=image, return_tensors="pt", padding=True) # Get outputs with torch.no_grad(): outputs = model(**inputs) # Compute probabilities logits_per_image = outputs.logits_per_image # this is the dot product of image and text features probs = logits_per_image.softmax(dim=1) # print(f"Probabilities: {probs[0].tolist()}") # print(f"Predicted class: {candidate_labels[probs.argmax()]}")from transformers import CLIPProcessor, CLIPModel from PIL import Image # Load CLIP model and processor model = CLIPModel.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32") processor = CLIPProcessor.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32") # Load your image image = Image.open("path/to/your/image.jpg") # Define candidate labels candidate_labels = ["a photo of a cat", "a photo of a dog", "a photo of a car"] # Process inputs inputs = processor(text=candidate_labels, images=image, return_tensors="pt", padding=True) # Get outputs with torch.no_grad(): outputs = model(**inputs) # Compute probabilities logits_per_image = outputs.logits_per_image # this is the dot product of image and text features probs = logits_per_image.softmax(dim=1) # print(f"Probabilities: {probs[0].tolist()}") # print(f"Predicted class: {candidate_labels[probs.argmax()]}")

-

Creative Content Generation & Editing:

- Example: Artists, designers, and marketers can use tools like Stable Diffusion to generate unique images from text prompts ("a cyberpunk city at sunset, highly detailed, volumetric lighting") or to perform inpainting/outpainting (filling in missing parts or extending images).

- Tool Usage: Accessing Stable Diffusion via online interfaces or local installations (e.g.,

diffuserslibrary in Python).

-

Semantic Image Search and Retrieval:

- Example: Build a more intelligent image search engine for a large media archive. Instead of keyword matching, encode all images and search queries into CLIP embeddings. Queries like "a serene landscape with a lone tree" will retrieve visually and semantically similar images, even if those images weren't tagged with those exact keywords.

-

Robust Feature Extraction for Downstream Tasks:

- Example: For tasks where fine-tuning a full foundation model is overkill or computationally too expensive (e.g., small embedded systems), you can use the frozen backbone of a pre-trained ViT or CLIP model as a powerful feature extractor. The embeddings produced by these models are highly generalizable and can be fed into simpler classifiers (SVM, XGBoost) or used for clustering.

-

Domain Adaptation with Limited Data:

- Example: In specialized domains like medical imaging or agricultural inspection, labeled data is scarce. Foundation models provide a strong initialization. Fine-tuning a MAE-pretrained ViT on a small dataset of X-ray images for disease detection will likely outperform training a CNN from scratch.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

While foundation models offer immense promise, they also bring significant challenges and open avenues for future research:

- Computational Cost: Training these models from scratch requires astronomical computational resources (thousands of GPUs for weeks), limiting access to a handful of large organizations. This necessitates a focus on efficient architectures, distributed training, and making pre-trained models widely available.

- Data Requirements: While SSL reduces the need for labeled data, it still demands vast amounts of unlabeled data. Curating and managing these massive datasets is a non-trivial task.

- Bias and Fairness: Foundation models learn from the data they are trained on. If this data contains societal biases (e.g., underrepresentation of certain demographics, stereotypical portrayals), the models will inherit and amplify these biases, leading to unfair or discriminatory outcomes in real-world applications. Addressing bias and ensuring fairness is a critical ethical and technical challenge.

- Interpretability and Explainability: Understanding why these complex models make certain decisions remains a significant hurdle. Tools to visualize attention maps and feature activations are emerging, but truly interpretable foundation models are an active area of research.

- Efficiency for Deployment: The sheer size of these models makes deployment on edge devices (smartphones, IoT sensors) or in real-time, low-latency applications challenging. Techniques like quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation are crucial for making them more efficient.

- Unified Architectures and "World Models": The long-term vision is to develop truly unified architectures that can process and understand multiple modalities (vision, language, audio, robotics, sensor data) simultaneously, moving towards more general-purpose "world models" that can reason about and interact with their environment.

Conclusion: A Visionary Future

The emergence of foundation models, particularly Vision Transformers and their multimodal counterparts, marks a profound shift in computer vision. We are moving away from task-specific model design towards general-purpose, scalable architectures capable of learning rich, transferable representations from vast amounts of data. This new era empowers practitioners with unprecedented capabilities for zero-shot learning, creative content generation, and robust feature extraction, democratizing access to cutting-edge AI.

However, with great power comes great responsibility. Addressing the challenges of computational cost, data bias, and interpretability will be crucial as these models become increasingly integrated into our daily lives. The journey is far from over; the convergence of vision, language, and other modalities promises an even more exciting future, where AI systems can perceive, understand, and interact with the world in ways we are only just beginning to imagine. The foundation has been laid; now it's time to build.