Foundation Models in Computer Vision: The Rise of Transformers Over CNNs

Explore the revolutionary impact of Foundation Models and the Transformer architecture on Computer Vision, challenging the long-standing dominance of Convolutional Neural Networks. Discover how these advancements are reshaping how machines interpret visual data.

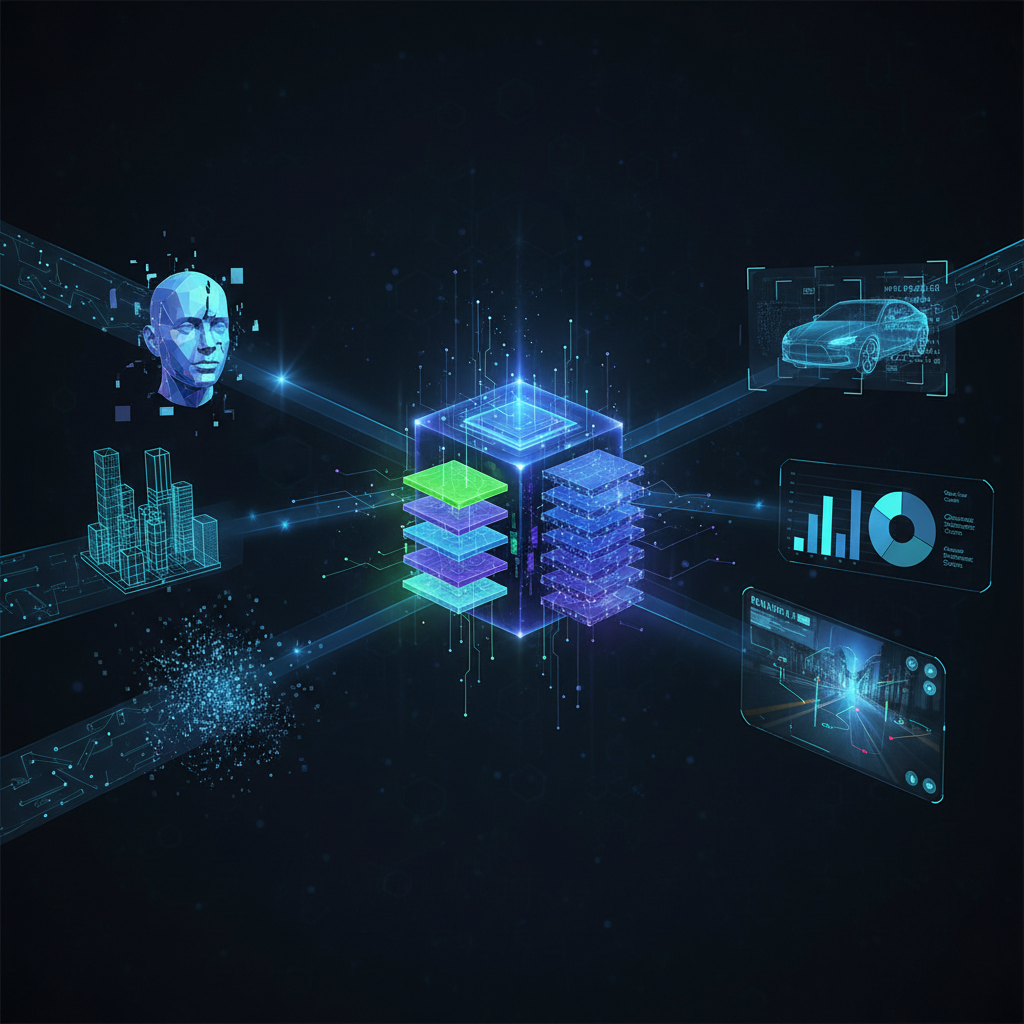

The landscape of artificial intelligence is in a constant state of flux, with paradigm shifts occurring at an accelerated pace. Just as Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and GPT-4 have fundamentally reshaped Natural Language Processing (NLP), a similar revolution is underway in Computer Vision. At the heart of this transformation are Foundation Models, particularly those built upon the Transformer architecture, ushering in an exciting new era for how machines "see" and interpret the world.

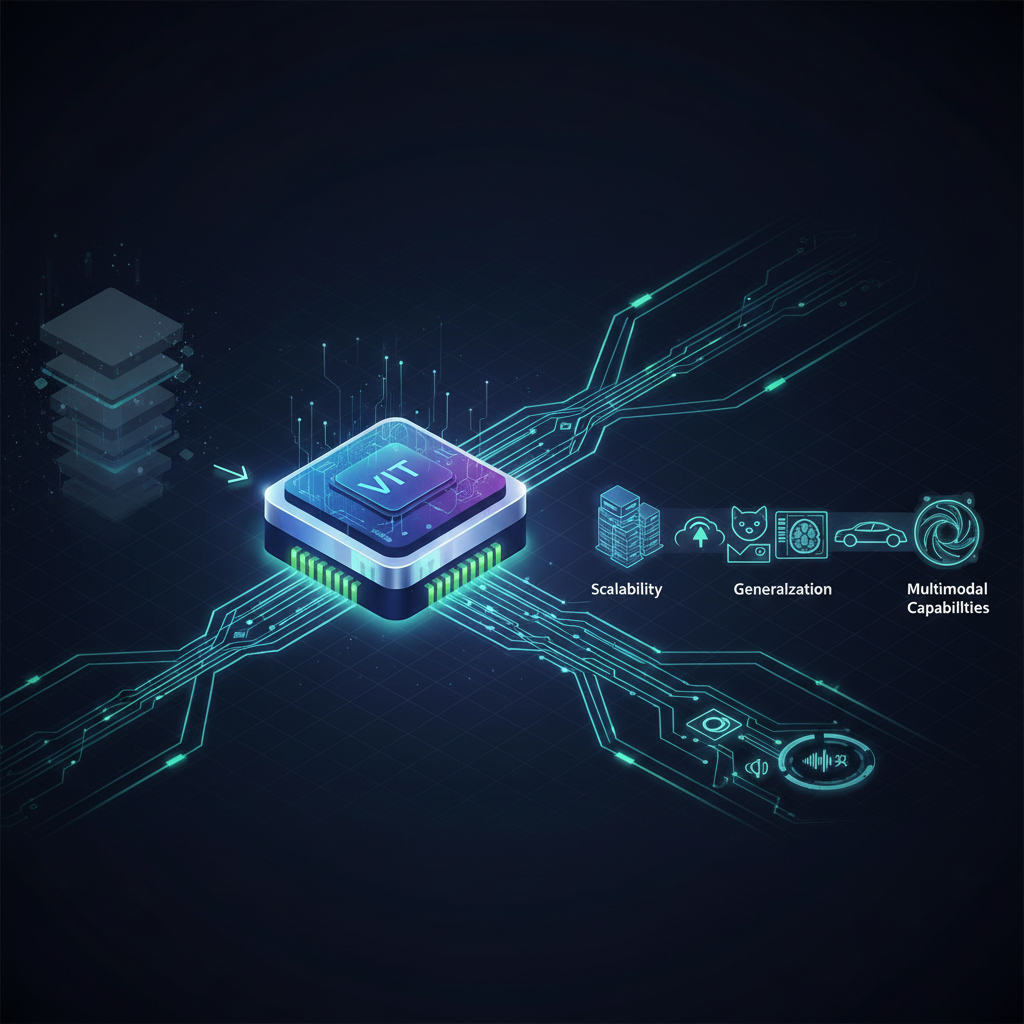

For decades, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) reigned supreme in computer vision, proving incredibly effective for tasks ranging from image classification to object detection. Their hierarchical structure, with local receptive fields and weight sharing, seemed perfectly suited for processing visual data. However, the emergence of the Transformer architecture, originally designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks in NLP, has challenged this long-held dominance, demonstrating unprecedented scalability, generalization, and multimodal capabilities when applied to images.

This shift isn't just an academic curiosity; it's profoundly impacting real-world applications across industries. From generating photorealistic images and understanding complex visual scenes to powering advanced medical diagnostics and autonomous systems, Foundation Models are redefining the boundaries of what's possible in computer vision. This blog post will delve into the core concepts, key developments, and practical implications of this exciting new frontier.

The Dawn of Vision Transformers (ViTs): An Image is Worth 16x16 Words

The seminal paper "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale" by Dosovitskiy et al. (2020) marked a pivotal moment. It boldly demonstrated that the Transformer architecture, without any inherent convolutional layers, could achieve state-of-the-art performance on image classification tasks, provided it was trained on sufficiently large datasets.

How ViTs Work: Deconstructing the Image

The core idea behind a Vision Transformer is surprisingly straightforward, drawing a direct analogy from NLP:

- Patching the Image: Instead of processing an image pixel by pixel or through convolutional filters, a ViT first divides the input image into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels). Each patch is treated like a "word" or "token" in a sentence.

- Linear Embedding: Each 2D image patch is then flattened into a 1D vector. A linear projection (a simple fully connected layer) maps these vectors into a higher-dimensional embedding space, creating a sequence of patch embeddings.

- Positional Encoding: Just as words in a sentence have an order, image patches have a spatial arrangement. To retain this crucial positional information, learnable positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings. This allows the model to understand where each patch is located relative to others.

- Class Token: An additional, learnable "class token" embedding is prepended to the sequence of patch embeddings. This token serves as a global representation of the entire image and is ultimately used for the final classification task.

- Transformer Encoder: The combined sequence of (class token + patch embeddings + positional encodings) is then fed into a standard Transformer encoder. This encoder consists of multiple layers, each containing a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward network.

- Self-Attention: This mechanism allows each patch embedding to attend to all other patch embeddings, effectively capturing global dependencies and relationships across the entire image. Unlike CNNs that have local receptive fields, self-attention enables the model to integrate information from distant parts of the image directly.

- Feed-Forward Networks: These layers apply non-linear transformations to the attention outputs, further processing the learned representations.

- Classification Head: Finally, the output embedding corresponding to the "class token" from the last Transformer encoder layer is passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) head for classification.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from einops.layers.torch import EinMix as Rearrange, EinMix

# Simplified ViT Patch Embedding

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.proj(x) # (B, E, H', W') where H'=W'=img_size/patch_size

x = x.flatten(2) # (B, E, N_patches)

x = x.transpose(1, 2) # (B, N_patches, E)

return x

# Conceptual ViT forward pass snippet (simplified)

# Assuming a full Transformer encoder is defined elsewhere

# from transformers import ViTModel # for actual implementation

# Example usage:

# img_size = 224

# patch_size = 16

# in_channels = 3

# embed_dim = 768

# batch_size = 1

# patch_embedder = PatchEmbedding(img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim)

# dummy_input = torch.randn(batch_size, in_channels, img_size, img_size)

# patch_embeddings = patch_embedder(dummy_input)

# class_token = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, 1, embed_dim))

# class_token = class_token.expand(batch_size, -1, -1)

# tokens = torch.cat((class_token, patch_embeddings), dim=1)

# positional_embeddings = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, tokens.shape[1], embed_dim))

# tokens = tokens + positional_embeddings

# # tokens would then be passed to a Transformer Encoder

# # output = transformer_encoder(tokens)

# # final_classification_output = output[:, 0] # Class token output

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from einops.layers.torch import EinMix as Rearrange, EinMix

# Simplified ViT Patch Embedding

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.proj(x) # (B, E, H', W') where H'=W'=img_size/patch_size

x = x.flatten(2) # (B, E, N_patches)

x = x.transpose(1, 2) # (B, N_patches, E)

return x

# Conceptual ViT forward pass snippet (simplified)

# Assuming a full Transformer encoder is defined elsewhere

# from transformers import ViTModel # for actual implementation

# Example usage:

# img_size = 224

# patch_size = 16

# in_channels = 3

# embed_dim = 768

# batch_size = 1

# patch_embedder = PatchEmbedding(img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim)

# dummy_input = torch.randn(batch_size, in_channels, img_size, img_size)

# patch_embeddings = patch_embedder(dummy_input)

# class_token = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, 1, embed_dim))

# class_token = class_token.expand(batch_size, -1, -1)

# tokens = torch.cat((class_token, patch_embeddings), dim=1)

# positional_embeddings = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, tokens.shape[1], embed_dim))

# tokens = tokens + positional_embeddings

# # tokens would then be passed to a Transformer Encoder

# # output = transformer_encoder(tokens)

# # final_classification_output = output[:, 0] # Class token output

Code Snippet: Simplified Patch Embedding for ViT. In actual implementations like Hugging Face's transformers library, the patch embedding and positional encoding are integrated within the ViTModel.

The key insight of ViTs was that, given enough data, the self-attention mechanism could learn powerful visual representations that were competitive with, or even superior to, CNNs. However, ViTs initially struggled with smaller datasets, where CNNs still held an advantage, highlighting their data hungry nature.

Overcoming Data Hunger: The Rise of Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)

The success of ViTs on massive datasets like JFT-300M (300 million images) underscored a challenge: obtaining such vast amounts of labeled data is expensive and often impractical. This led to a surge in research into Self-Supervised Learning (SSL), a paradigm where models learn rich representations from unlabeled data by solving "pretext tasks."

Key SSL Methods for Vision Transformers:

-

Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Introduced by He et al. (2021), MAE is a highly influential SSL method inspired by BERT in NLP.

- Concept: A large portion of an image's patches (e.g., 75%) are randomly masked out. A ViT encoder processes only the visible patches, and a lightweight decoder then attempts to reconstruct the original pixel values of the masked patches.

- Why it works: To reconstruct missing pixels, the model must learn to understand the semantic content and context of the visible patches. This forces it to learn meaningful, high-level representations rather than just low-level features.

- Efficiency: MAE is computationally efficient during pre-training because the encoder only processes a small fraction of the patches. The decoder is discarded after pre-training, making the fine-tuned model lean.

-

DINO / DINOv2: (Caron et al., 2021; Oquab et al., 2023) DINO (Self-Distillation with No Labels) leverages knowledge distillation in a self-supervised manner.

- Concept: It trains a "student" ViT to match the output of a "teacher" ViT, where the teacher is an exponentially moving average (EMA) of the student's weights. Both models receive different augmented views of the same image. The goal is for the student to produce similar embeddings for different views of the same image, without requiring explicit labels.

- Emerging Properties: DINO models are remarkable for learning features that exhibit explicit semantic segmentation properties, even without being trained for segmentation. They can spontaneously segment objects and parts of objects, making them powerful for downstream tasks.

- DINOv2: This successor scales DINO to even larger datasets (e.g., 1.2 billion images) and incorporates architectural improvements, yielding exceptionally robust and general-purpose visual features.

-

Contrastive Learning (e.g., MoCo v3, SimCLR v2 adapted for ViTs): While initially popular with CNNs, contrastive learning has also been adapted for ViTs.

- Concept: The model learns to pull "positive pairs" (different augmented views of the same image) closer together in the embedding space while pushing "negative pairs" (embeddings of different images) further apart.

- ViT Adaptation: The core contrastive loss remains, but the backbone architecture is a ViT. This helps the ViT learn discriminative features by distinguishing between similar and dissimilar images.

SSL has been a game-changer, allowing ViTs to learn powerful, general-purpose visual features from vast quantities of readily available unlabeled data. These pre-trained SSL models then serve as excellent backbones for fine-tuning on specific downstream tasks, often requiring significantly less labeled data to achieve state-of-the-art results.

Bridging the Gap: Hierarchical Vision Transformers

While standard ViTs excel at capturing global relationships, their fixed-size patch processing and quadratic complexity of self-attention with respect to image size can be limiting. They sometimes struggle with fine-grained local details and are computationally expensive for high-resolution images. This led to the development of Hierarchical Vision Transformers.

Swin Transformer: A Hybrid Approach

The Swin Transformer ("Swin" stands for Shifted Windows), introduced by Liu et al. (2021), elegantly addresses these limitations. It combines the best aspects of CNNs (hierarchical feature maps, local processing) with the power of Transformers (self-attention).

- Hierarchical Feature Maps: Similar to CNNs, Swin Transformers build hierarchical feature representations. They start with small patches and then progressively merge adjacent patches in deeper layers, creating larger "patches" that represent broader regions of the image. This allows the model to capture features at different scales.

- Window-based Self-Attention: To reduce computational cost and introduce locality, Swin Transformers compute self-attention only within non-overlapping local windows. This changes the quadratic complexity to linear with respect to image size within each window.

- Shifted Window Mechanism: To enable cross-window connections and allow information flow between different windows, the windows are shifted between successive layers. This ensures that patches from different windows can interact, preventing the model from being too localized.

The Swin Transformer has become an incredibly popular and versatile backbone, achieving state-of-the-art results across a wide range of vision tasks, including classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation, often outperforming both traditional ViTs and advanced CNNs.

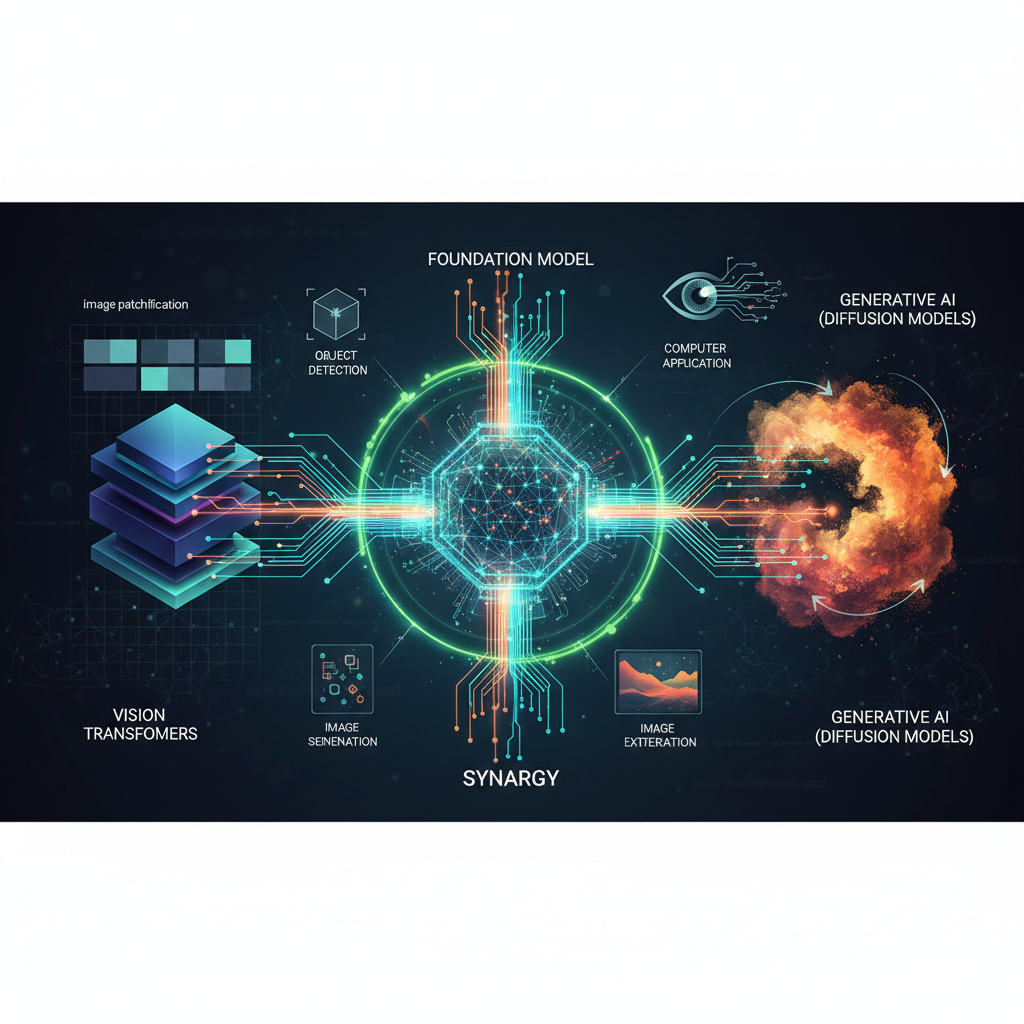

The Multimodal Frontier: Vision-Language Foundation Models

Perhaps one of the most exciting developments is the convergence of vision and language through multimodal Foundation Models. By training on vast datasets of image-text pairs, these models learn to understand the semantic relationships between visual content and natural language descriptions, unlocking unprecedented capabilities.

Key Multimodal Models:

-

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training): (Radford et al., 2021) OpenAI's CLIP was a groundbreaking model that learned to connect images and text.

- Concept: CLIP trains two separate encoders—a Vision Transformer for images and a text Transformer for text—simultaneously. It learns by contrasting 400 million image-text pairs, optimizing to bring embeddings of matching image-text pairs closer together and push non-matching pairs further apart.

- Zero-Shot Capabilities: The magic of CLIP lies in its ability to perform "zero-shot" classification. Given an image, it can classify it into any category simply by comparing the image's embedding with the embeddings of text descriptions of those categories (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog"). This eliminates the need for task-specific labeled training data.

-

Generative Models (DALL-E 2 / Stable Diffusion): These models leverage the power of vision-language understanding to generate high-quality images from text descriptions.

- Mechanism: They often use a text encoder (like CLIP's text encoder) to convert a text prompt into a rich embedding. This embedding then conditions a diffusion model, which iteratively refines a noisy image into a coherent, high-fidelity image that matches the text description.

- Impact: These models have democratized image creation, enabling users to generate complex and artistic imagery with simple text prompts, revolutionizing fields like graphic design, advertising, and digital art.

-

Multimodal LLMs (Flamingo, BLIP, LLaVA): These models integrate vision encoders with large language models to enable more complex reasoning and interaction.

- Concept: They combine a pre-trained vision model (e.g., a ViT or Swin Transformer) with a large language model. This allows them to process both visual input (e.g., an image) and text input (e.g., a question about the image) and generate coherent, contextually relevant text responses.

- Applications: Visual Question Answering (VQA), image captioning, multimodal conversational AI, and even complex reasoning tasks where both visual and textual cues are necessary.

These multimodal foundation models represent a significant step towards more human-like AI, capable of understanding and generating content across different modalities.

Practical Applications and Implications for Practitioners

The emergence of Foundation Models in computer vision has profound implications for practitioners across various domains.

1. Transfer Learning and Fine-tuning: The New Standard

Pre-trained ViTs, Swin Transformers, MAE, and DINOv2 models are the new go-to backbones for computer vision tasks.

- Benefit: Instead of training models from scratch on limited datasets, practitioners can take a pre-trained Foundation Model and fine-tune it on their specific, often smaller, labeled dataset. This dramatically reduces the amount of labeled data required, computational cost, and training time, while often achieving superior performance.

- Example: A medical imaging specialist can fine-tune a DINOv2 pre-trained ViT on a dataset of X-rays to detect specific anomalies, achieving high accuracy even with a relatively small number of labeled X-rays.

2. Zero-shot and Few-shot Learning: Unlocking New Possibilities

Models like CLIP enable classification and retrieval tasks without requiring explicit training on target classes.

- Benefit: This is invaluable for rapidly deploying models in new domains where labeled data is scarce or non-existent, or for handling dynamic classification tasks where new categories emerge frequently.

- Example: An e-commerce platform can use CLIP to categorize newly uploaded product images into fine-grained categories (e.g., "vintage leather handbag," "modern minimalist vase") without needing to collect and label thousands of examples for each new category. It can also power visual search, allowing users to find similar items based on an image query.

3. Generative AI: Content Creation and Synthetic Data

Understanding the principles behind diffusion models conditioned by vision-language embeddings is crucial for content creation and data augmentation.

- Benefit: Practitioners can leverage these models for generating diverse and high-quality synthetic data, which can be used to augment real datasets, improve model robustness, or create entirely new visual assets.

- Example: Game developers can use Stable Diffusion to generate unique textures, character designs, or environmental assets based on text prompts, accelerating their creative workflow. Researchers can generate synthetic medical images to train models for rare diseases, overcoming data privacy and scarcity issues.

4. Multimodal AI Systems: Holistic Understanding

Building systems that can understand and reason about both visual and textual information is becoming increasingly important.

- Benefit: This allows for the creation of more intelligent and intuitive AI applications that can interact with users in a more natural way.

- Example: An accessibility tool could use a multimodal LLM to describe complex visual scenes to visually impaired users, answering follow-up questions about objects, people, and actions within the scene. Automated content moderation systems can analyze both images/videos and accompanying text to detect harmful content more accurately.

5. Research and Development: A Fertile Ground

This field is incredibly active, offering numerous opportunities for innovation.

- Benefit: Researchers and developers can contribute by exploring more efficient architectures, developing novel self-supervised learning objectives, or applying these powerful models to new, challenging domains like robotics, scientific imaging, or environmental monitoring.

- Example: Developing specialized ViT architectures for satellite imagery analysis to monitor climate change, or integrating Foundation Models into robotic systems for enhanced perception and navigation in unstructured environments.

6. Ethical Considerations: Responsibility in Power

The immense power of these models also brings significant ethical responsibilities.

- Challenge: Bias in training data can lead to biased model outputs (e.g., misidentifying individuals from certain demographics). The potential for misuse (e.g., deepfakes, surveillance) and the substantial environmental impact of training large models are critical concerns.

- Implication: Practitioners must be acutely aware of these issues, actively work to mitigate biases, ensure responsible deployment, and advocate for ethical AI development practices. This includes careful data curation, rigorous fairness evaluations, and transparency in model capabilities and limitations.

Conclusion: The Future is Foundational

The era of Foundation Models in computer vision, spearheaded by Vision Transformers and their sophisticated successors, marks a pivotal moment in AI. These models have not only challenged long-held assumptions about how machines perceive the world but have also unlocked unprecedented capabilities in generalization, scalability, and multimodal understanding.

From the foundational concept of patching images for self-attention to the advanced techniques of self-supervised learning (MAE, DINOv2) and hierarchical architectures (Swin Transformer), we've seen a rapid evolution. The integration of vision and language through models like CLIP and the rise of generative AI with diffusion models have further expanded the horizons, blurring the lines between different AI subfields.

For practitioners, this revolution offers powerful tools for building more robust, efficient, and intelligent computer vision systems. The ability to leverage pre-trained models, perform zero-shot learning, and engage with multimodal data significantly lowers the barrier to entry for achieving state-of-the-art results. However, with great power comes great responsibility. Navigating the ethical landscape, addressing biases, and ensuring responsible deployment will be paramount as these foundational models continue to shape our visual world. The journey has just begun, and the future of computer vision, built on these powerful foundations, promises to be nothing short of transformative.