Foundation Models in Computer Vision: The Rise of Vision Transformers and Multimodal AI

Explore the revolution in Computer Vision driven by Foundation Models like Vision Transformers (ViTs) and multimodal learning. This post delves into how these models, trained on vast datasets, are reshaping AI capabilities, moving beyond traditional CNNs to achieve unprecedented performance and generalizability.

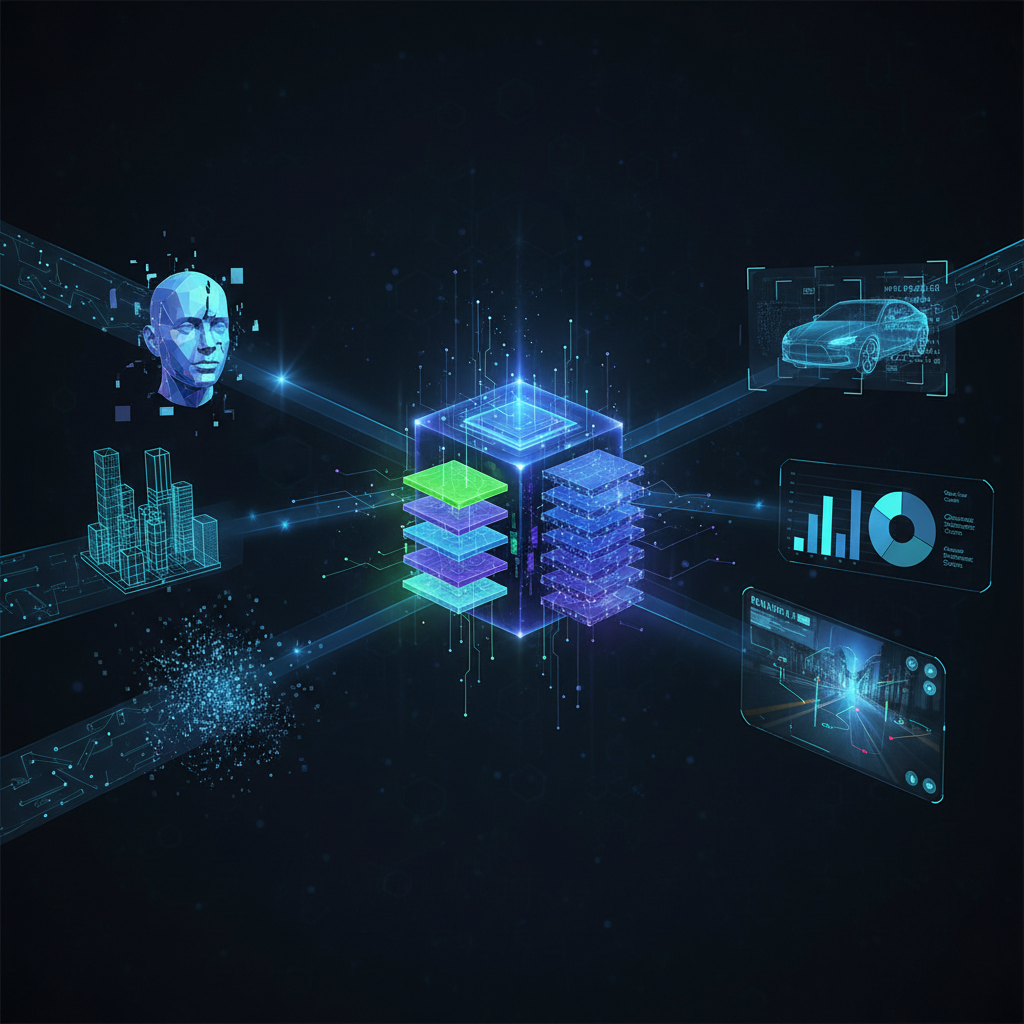

The landscape of artificial intelligence is in a constant state of flux, with breakthroughs regularly redefining what's possible. In recent years, the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) witnessed a seismic shift with the advent of large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3/4, which demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in understanding and generating human language. Now, a similar revolution is unfolding in Computer Vision, driven by the emergence of Foundation Models, particularly Vision Transformers (ViTs) and the powerful paradigm of multimodal learning.

This shift marks a departure from traditional convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures that have dominated computer vision for decades. Foundation models, trained on vast and diverse datasets, are learning highly generalizable representations, enabling them to tackle a myriad of downstream tasks with remarkable efficiency and performance. This blog post will delve into the core concepts, architectural innovations, practical applications, and future implications of this exciting new era in computer vision.

The Paradigm Shift: From CNNs to Transformers in Vision

For years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were the undisputed champions of computer vision. Their hierarchical structure, local receptive fields, and weight sharing properties made them incredibly effective at capturing spatial hierarchies and patterns in images. However, their inductive biases, while beneficial for image-specific tasks, also limited their ability to capture long-range dependencies across an entire image effectively.

The Transformer architecture, initially introduced for sequence-to-sequence tasks in NLP, shattered performance records by leveraging a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different parts of an input sequence relative to each other. The core idea was that instead of processing data sequentially or locally, the model could attend to all parts of the input simultaneously, capturing global relationships.

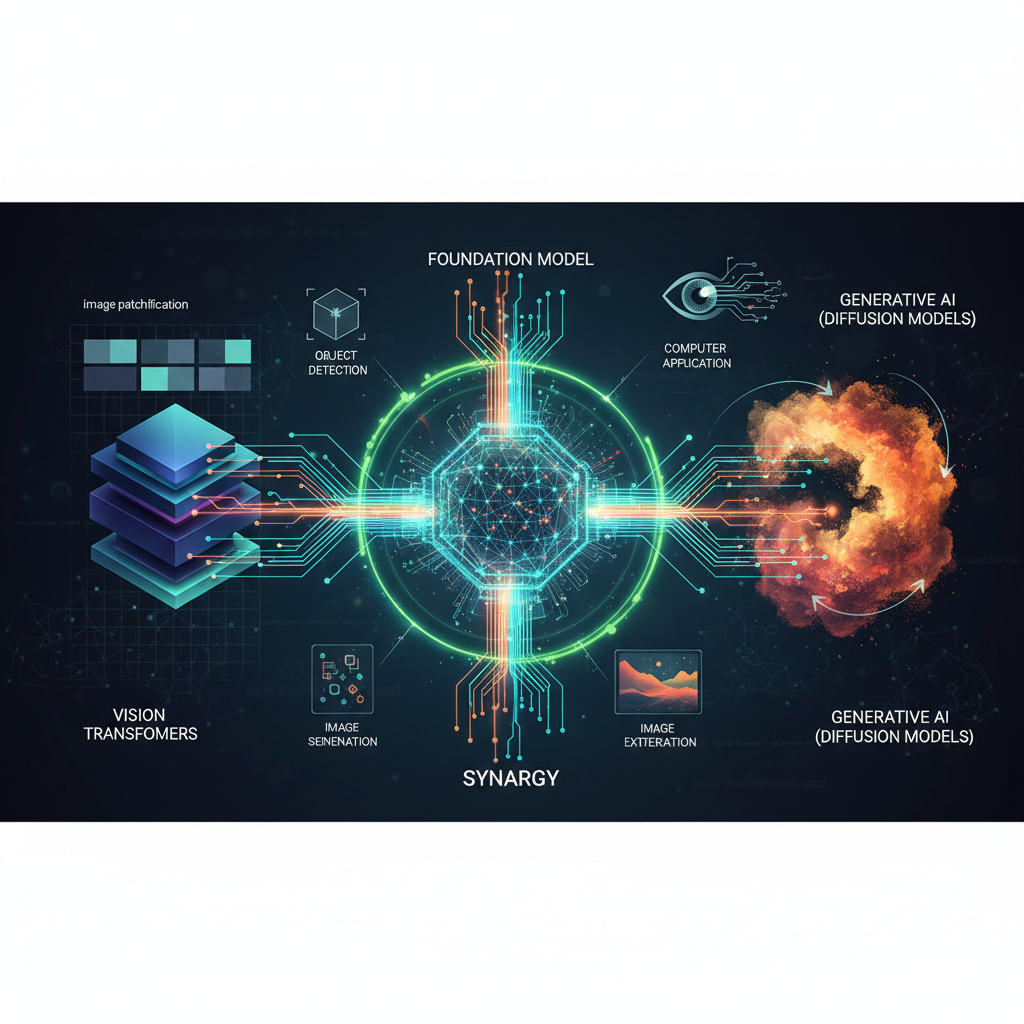

Vision Transformers (ViTs): Bringing Self-Attention to Images

The seminal paper "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale" (Dosovitskiy et al., 2020) demonstrated that Transformers could be directly applied to image data with impressive results, especially when pre-trained on large datasets. The core idea behind a Vision Transformer (ViT) is surprisingly simple yet profoundly effective:

- Patch Embedding: An input image is first divided into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels). Each patch is then flattened into a 1D vector.

- Linear Projection: These flattened patch vectors are linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space. This is analogous to how words are converted into token embeddings in NLP.

- Positional Encoding: Since Transformers inherently lack information about the spatial arrangement of input tokens, positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings. This allows the model to understand the relative positions of the patches within the original image.

- Transformer Encoder: The sequence of patch embeddings (along with a special

[CLS]token, similar to BERT, used for classification) is then fed into a standard Transformer encoder stack. This stack consists of multiple layers, each comprising a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) module and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN).- Multi-Head Self-Attention: This is the heart of the Transformer. It allows each patch to attend to every other patch in the image, learning global dependencies and relationships between different parts of the image, regardless of their spatial distance.

- Feed-Forward Network: A simple neural network applied independently to each position, further processing the attended information.

- Classification Head: Finally, the output corresponding to the

[CLS]token (or a global average pooling of all patch outputs) is fed into a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) head for classification.

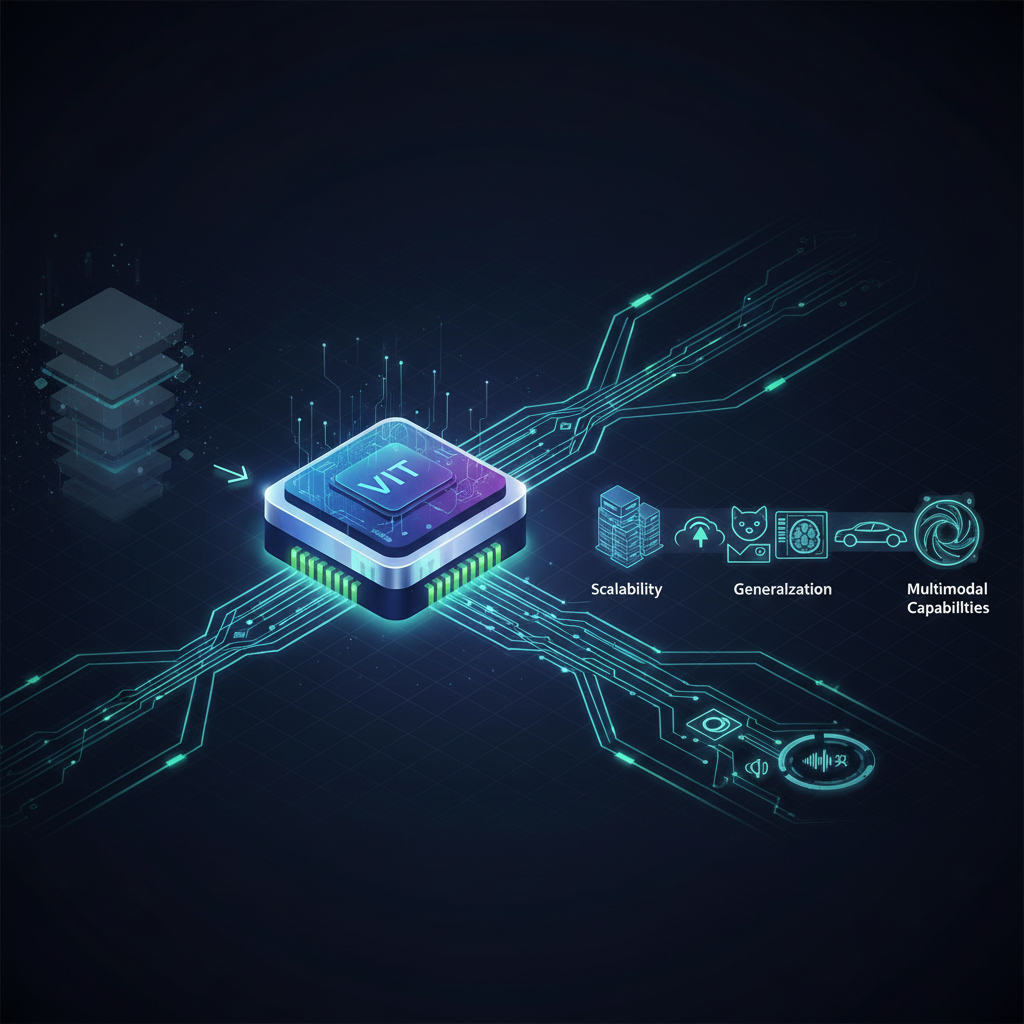

Advantages of ViTs:

- Global Receptive Field: Unlike CNNs, which build up a global understanding through successive layers of local convolutions, ViTs inherently process the entire image globally from the first layer, thanks to self-attention. This allows them to capture long-range dependencies more effectively.

- Scalability: Transformers are highly scalable with increasing data and model size, often leading to better performance.

- Reduced Inductive Bias: While CNNs benefit from inductive biases like locality and translation equivariance, ViTs have fewer such biases, making them more flexible and potentially capable of learning more diverse patterns from massive datasets.

Challenges of ViTs:

- Data Hungry: Initially, ViTs required very large datasets for pre-training to outperform CNNs. Without sufficient data, their performance could lag.

- Computational Cost: The self-attention mechanism computes attention scores between every pair of tokens, leading to a quadratic complexity with respect to the number of patches. For high-resolution images, this can be computationally expensive.

Key ViT Variants and Innovations:

To address the challenges and enhance the capabilities of the original ViT, several innovative variants have emerged:

- DeiT (Data-efficient Image Transformers): Introduced a teacher-student strategy using distillation tokens, allowing ViTs to achieve competitive performance even with smaller training datasets, mitigating the "data hungry" issue.

- Swin Transformers: Revolutionized ViT efficiency by introducing hierarchical feature maps and "shifted windows." Instead of computing self-attention globally, Swin Transformers compute it within local windows, and then shift these windows in successive layers to allow for cross-window connections. This reduces computational complexity to linear with respect to image size, making them highly efficient for high-resolution images and dense prediction tasks (like segmentation).

- MAE (Masked Autoencoders): Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, MAE pre-trains ViTs by masking a large portion of image patches and then reconstructing the missing pixels. This self-supervised approach has proven incredibly effective, allowing ViTs to learn rich visual representations from unlabeled data.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) for Vision: Unlocking the Power of Unlabeled Data

One of the biggest bottlenecks in traditional supervised learning is the need for vast amounts of meticulously labeled data. This is expensive, time-consuming, and often requires expert knowledge. Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) offers a powerful solution by creating "pseudo-labels" from the data itself, allowing models to learn robust representations from unlabeled datasets. This has been a critical enabler for the success of foundation models in vision.

Common SSL Approaches:

-

Contrastive Learning:

- Core Idea: Learn an embedding space where augmented versions of the same image are pulled closer together, while augmented versions of different images are pushed farther apart.

- Examples:

- SimCLR: Uses multiple augmented views of an image and a contrastive loss function (NT-Xent) to maximize agreement between positive pairs (different augmentations of the same image) and minimize agreement with negative pairs (augmentations of different images).

- MoCo (Momentum Contrast): Addresses the need for a large number of negative samples by maintaining a momentum encoder and a queue of negative samples, making training more stable and efficient.

- BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent): Achieves state-of-the-art results without explicit negative pairs, relying on two interacting networks (online and target) that learn from each other through a prediction head and a momentum-updated target network.

-

Masked Image Modeling (MIM):

- Core Idea: Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, MIM involves masking out portions of an input image and then training the model to reconstruct the missing information.

- Example:

- MAE (Masked Autoencoders): As mentioned earlier, MAE masks a high percentage (e.g., 75%) of image patches and trains a ViT encoder-decoder architecture to reconstruct the original pixel values of the masked patches. This forces the encoder to learn meaningful representations from the visible patches.

-

Knowledge Distillation:

- Core Idea: Transfer knowledge from a "teacher" model to a "student" model. In SSL, this can be done without explicit labels.

- Example:

- DINO (Self-Distillation with No Labels): Uses a teacher-student setup where both are ViTs. The teacher's weights are a momentum average of the student's weights. The student is trained to match the output distribution of the teacher on different augmentations of the same image, without requiring negative samples or a complex contrastive loss.

The impact of SSL is profound: it allows foundation models to be pre-trained on massive, diverse datasets like ImageNet-21K or even larger collections of unlabeled images, leading to highly robust and generalizable feature extractors that can be fine-tuned for specific tasks with far less labeled data.

Multimodal Foundation Models: Bridging Vision and Language

Perhaps one of the most exciting developments is the rise of multimodal foundation models that can understand and generate content across different modalities, particularly vision and language. These models are not just analyzing images or text in isolation; they are learning joint representations that capture the intricate relationships between them, leading to entirely new capabilities.

CLIP: Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) by OpenAI is a landmark achievement in multimodal learning.

- Mechanism: CLIP is trained on an enormous dataset of 400 million image-text pairs scraped from the internet. It simultaneously trains an image encoder (a ResNet or ViT) and a text encoder (a Transformer) to embed corresponding image-text pairs close together in a shared, high-dimensional latent space. The training objective is to maximize the cosine similarity between correct image-text pairs and minimize it for incorrect pairs.

- Applications:

- Zero-shot Classification: One of CLIP's most powerful features. Given an image, you can classify it by comparing its embedding to the embeddings of various text descriptions (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog," "a photo of a car"). The model assigns the image to the class whose text embedding is closest. This allows classification of novel categories without any specific training data for those categories.

- Image Retrieval: Find images matching a text query, or find text descriptions matching an image.

- Image Generation (as a component): CLIP's ability to measure the semantic similarity between text prompts and generated images makes it an invaluable component in text-to-image generation models, guiding the generation process towards visually and semantically coherent outputs.

Text-to-Image Generation: DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney

The explosion of high-quality text-to-image generation models has captivated the public imagination and revolutionized creative workflows. These models leverage the power of multimodal understanding, often incorporating components like CLIP.

- Mechanism: Most modern text-to-image models (like DALL-E 2, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney) are built upon Diffusion Models.

- Diffusion Process: A diffusion model learns to reverse a process of gradually adding noise to an image until it becomes pure noise. During generation, it starts with random noise and iteratively denoises it, guided by a text prompt, to produce a coherent image.

- Text Conditioning: The text prompt is encoded into an embedding (often using a CLIP text encoder or similar) which then conditions the denoising process, ensuring the generated image aligns semantically with the input text.

- Impact: These models are transforming content creation, enabling artists, designers, and marketers to rapidly prototype ideas, generate unique visuals, and explore creative concepts that were previously impossible or prohibitively expensive.

Visual Question Answering and Multimodal Dialogue: Flamingo, BLIP, LLaVA

Beyond generating images, the next frontier is enabling AI to "see," "understand," and "converse" about images in a human-like manner. This involves integrating vision models with large language models.

- Flamingo (DeepMind): A pioneering model that combines a frozen pre-trained vision encoder (e.g., a ViT) with a frozen pre-trained LLM. It uses "perceiver-resampler" modules to convert visual features into tokens that the LLM can understand, allowing for few-shot learning on multimodal tasks like visual question answering (VQA) and image captioning.

- BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training): Focuses on robust pre-training for vision-language understanding and generation. It uses a novel "Multimodal Mixture of Experts" (MoME) architecture and a "CapFilt" dataset bootstrapping strategy to generate high-quality captions for web images, improving generalization.

- LLaVA (Large Language and Vision Assistant): Integrates a visual encoder with a large language model (like LLaMA) to enable multimodal chat. It's trained on a new dataset of image-text instruction-following data, allowing it to perform tasks like answering questions about images, describing scenes, and even engaging in multimodal dialogue.

These models are paving the way for truly intelligent agents that can interact with the world through both sight and language, opening up possibilities for advanced robotics, accessibility tools, and more intuitive human-computer interfaces.

Transfer Learning and Fine-tuning Strategies

The power of foundation models lies in their ability to be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal effort, thanks to the rich representations learned during pre-training.

- Zero-shot Learning: As exemplified by CLIP, a model can perform a task (e.g., classification) on categories it has never explicitly seen during fine-tuning, relying solely on its general understanding of concepts learned during pre-training.

- Few-shot Learning: With just a handful of labeled examples for a new task, a pre-trained foundation model can be quickly adapted to achieve high performance, significantly reducing the data requirements compared to training from scratch.

- Prompt Engineering for Vision Models: Just as with LLMs, crafting effective text prompts is crucial for guiding generative vision models (e.g., "a photorealistic image of an astronaut riding a horse on the moon, cinematic lighting") or querying multimodal models for specific information.

- Adapter-based Fine-tuning: For very large foundation models, fine-tuning all parameters can be computationally expensive. Adapter layers are small, task-specific modules inserted into the pre-trained model. Only these adapter layers (and sometimes a small subset of the original model's parameters) are trained, making fine-tuning much more efficient while retaining most of the pre-trained knowledge.

Practical Applications and Implications

The advancements in Vision Transformers and multimodal learning are not confined to research labs; they are rapidly translating into real-world applications across diverse industries:

- Medical Imaging: Foundation models can accelerate diagnosis by identifying subtle anomalies in X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans. Their ability to learn from limited labeled data is particularly valuable in medical domains where annotations are scarce and expensive.

- Autonomous Driving: Enhanced perception systems leveraging ViTs can better understand complex road scenes, identify pedestrians, vehicles, and obstacles with greater accuracy and robustness under varying conditions. Multimodal models can integrate camera feeds with sensor data and navigation instructions.

- Robotics: Robots can achieve improved object recognition, scene understanding, and manipulation capabilities, leading to more intelligent and adaptable robotic systems for manufacturing, logistics, and service.

- Content Creation and Design: Text-to-image models are empowering artists and designers to generate novel concepts, rapidly iterate on designs, create custom assets, and even produce entire visual campaigns from simple text prompts.

- Industrial Inspection: Automated quality control systems can leverage foundation models to detect defects in products with high precision, reducing human error and increasing efficiency in manufacturing.

- Accessibility: Advanced image captioning and visual question answering models can provide richer descriptions of images for visually impaired users, enhancing their digital experience and access to information.

- Security and Surveillance: Improved object detection and anomaly recognition can enhance security systems, though this also raises important ethical considerations.

Ethical Considerations and Challenges

While the capabilities of foundation models are awe-inspiring, their rapid deployment also brings significant ethical challenges and considerations:

- Bias in Training Data: Foundation models are trained on massive datasets that often reflect societal biases present in the internet data they are scraped from. This can lead to models that perpetuate stereotypes, exhibit unfair performance across different demographic groups, or generate harmful content. Mitigating bias is a critical area of research.

- Misinformation and Deepfakes: The ability to generate highly realistic images and videos from text prompts raises concerns about the potential for creating convincing deepfakes, spreading misinformation, and manipulating public opinion.

- Copyright and Ownership: The use of vast amounts of existing images and artworks for training generative models has sparked debates about copyright infringement and fair use, particularly concerning the rights of artists whose work may have been used without explicit consent.

- Environmental Impact: Training these colossal models requires immense computational resources, leading to a significant carbon footprint. Research into more energy-efficient architectures and training strategies is crucial.

- Job Displacement: As AI capabilities advance, there are concerns about the potential impact on jobs, particularly in creative industries.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach involving responsible AI development, robust ethical guidelines, policy frameworks, and ongoing research into explainability, fairness, and safety.

Conclusion

The rise of Vision Transformers and multimodal foundation models marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of computer vision. By adopting the Transformer architecture and leveraging the power of self-supervised learning on massive datasets, these models have achieved unprecedented levels of generalization and performance. The integration of vision and language, exemplified by models like CLIP, DALL-E, and Flamingo, is unlocking entirely new forms of human-computer interaction and creative expression.

We are moving towards a future where AI systems can not only "see" but also "understand" and "reason" about the visual world in concert with language. For AI practitioners and enthusiasts, understanding these foundational shifts is not just about keeping up with the latest trends; it's about grasping the fundamental building blocks of the next generation of intelligent systems. The journey is far from over, with active research continuously pushing the boundaries, but one thing is clear: the era of powerful, general-purpose vision AI is here, and its impact will resonate across every facet of our digital and physical lives.